© Erika M. Sparby

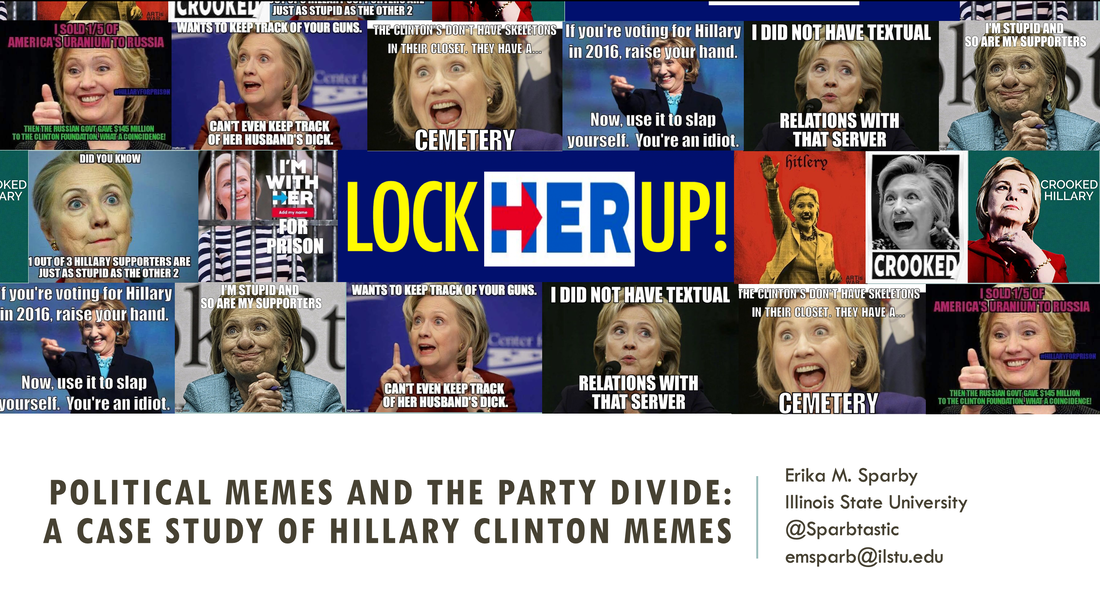

Political Memes and the Party Divide: A Case Study of Kim Davis and Hillary Clinton Memes

Adapted from a presentation at the University of Alabama Digital Rhetoric / Digital Media in the Post-Truth Age Symposium

|

A quick note before I get started. The problem with proposing papers months before researching and writing them is that often our trajectories change as our ideas develop. Such is the case with this presentation. Unfortunately, I won’t have time to talk about Kim Davis memes, but I am prepared to share some preliminary ideas in the Q&A for those interested. And so, onto my slightly retitled presentation: Political Memes and the Party Divide: A Case Study of Hillary Clinton Memes.

|

At this point in our sociocultural moment, we cannot ignore memes and their capacity to circulate, reflect, and create cultural meaning. These simple, mundane texts have the power to make us laugh, cry, think, and sometimes even act. Stephanie Vie (2014) has shown how something as simple as changing a Facebook profile image to display the Human Rights Campaign logo can show LGBTQ+ solidarity, Ryan Milner (2013) has shown that those who could not participate in the Occupy Wall Street movement in person created “I am the X%” memes to demonstrate their solidarity with (or opposition to) it, and An Xiao Mina (2019) has demonstrated how memes are integral to modern day activist movements.

During the 2016 U.S. Presidential election, memes were circulated in support of or opposition to political candidates, and many of these memes became key polarizing sources of disinformation. As a rhetorical meme scholar, I’m interested in how memes are used as vehicles for political disruption; as an intersectional feminist, I’m interested in how women are disproportionately affected by memetic representation; as an activist, I’m interested in how we can make meaningful interventions. As such, this presentation pulls these three threads together, examining Hillary Clinton memes to reveal how memes function as demagoguery and propaganda that aim to spread disinformation. I also wanted to bring in some memes with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Maxine Waters but in the interest of time could not. It really came down to, this is going to be kind of a surface level examination, and I’m okay with giving the old white lady the surface level treatment, but the women of color memes deserve a fuller look because there are so many more intersecting oppressions to unpack. I can talk some preliminary thoughts in the Q&A if anyone is interested.

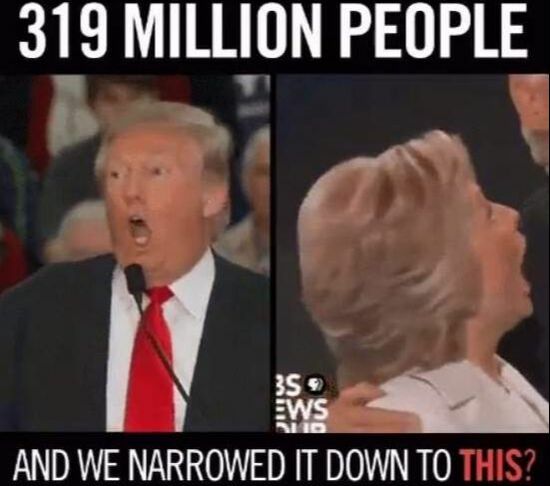

Before I begin, it might be useful to provide a working definition of memes, because they can take many forms. When Richard Dawkins (1976) coined the term long before the social web was even a conceivable reality, he defined it as cultural information spread from person to person (like genes, but with culture). With the rise of digital technologies we’ve moved well beyond this analogic definition, but the core—the transmission of cultural information—remains intact. When it comes to political memes from around the 2016 election, a number of both analog and digital memetic artifacts circulated, including MAGA hats, phrases like “basket of deplorables,” gifs of Trump tackling news logos, and image macro memes—the latter of which I will analyze in this presentation. These memes often depict recognizable political figures in the center, and the text can include anything from hostile invective or sharp critique to high praise or support. They are often light trolling at their most innocuous and downright inflammatory at their most dangerous. I use “innocuous” and “dangerous” here intentionally. These kinds of memes have the power to preclude possibilities for productive discourse, which in the heat of the 2016 election turned out to be quite dangerous to democracy.

Before I begin, it might be useful to provide a working definition of memes, because they can take many forms. When Richard Dawkins (1976) coined the term long before the social web was even a conceivable reality, he defined it as cultural information spread from person to person (like genes, but with culture). With the rise of digital technologies we’ve moved well beyond this analogic definition, but the core—the transmission of cultural information—remains intact. When it comes to political memes from around the 2016 election, a number of both analog and digital memetic artifacts circulated, including MAGA hats, phrases like “basket of deplorables,” gifs of Trump tackling news logos, and image macro memes—the latter of which I will analyze in this presentation. These memes often depict recognizable political figures in the center, and the text can include anything from hostile invective or sharp critique to high praise or support. They are often light trolling at their most innocuous and downright inflammatory at their most dangerous. I use “innocuous” and “dangerous” here intentionally. These kinds of memes have the power to preclude possibilities for productive discourse, which in the heat of the 2016 election turned out to be quite dangerous to democracy.

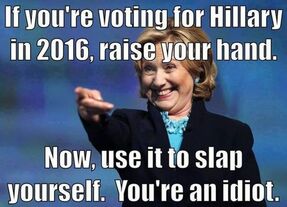

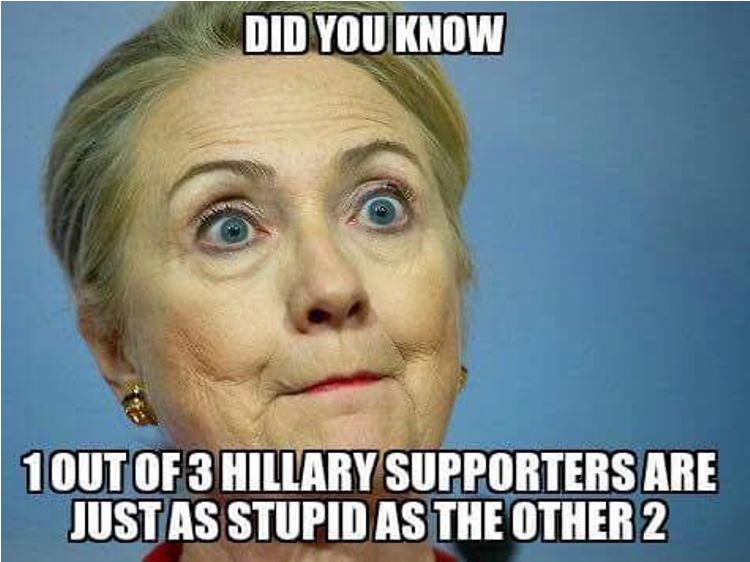

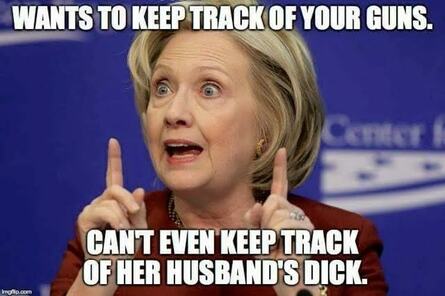

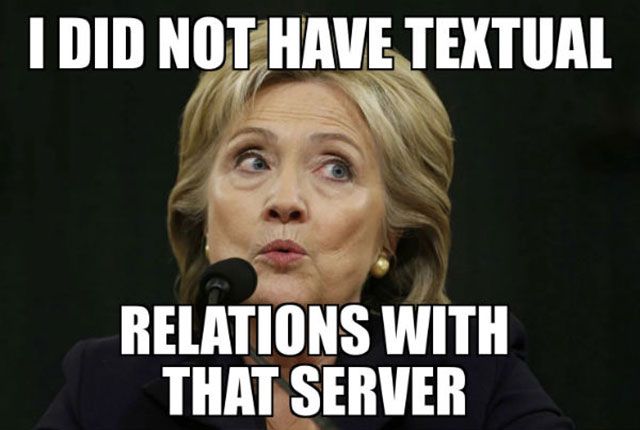

In addition, it’s no secret that women often get a short shrift when it comes to memetic representation. As I demonstrated in my dissertation, women are often depicted as objects of male fantasy, as undesirable, or as lacking intelligence (Sparby, 2017a). Something that all of these memes have in common is that they serve as indicators of what a heteronormative “good” woman is in a patriarchal society. Through memetic representation, women are told how it is acceptable to behave. This becomes the overarching message behind negative Hillary Clinton memes: not only is she is not a “good” woman, but as a woman she is unfit to run the country. These memes tend to fixate on things like her appearance, the infamous emails, her intelligence, and her husband’s infidelity. This is not a revelation. One of the main conversations that rose from the 2016 election is our tendency to fixate on woman candidates’ likeability instead of their capability to do the job. Memes are part of this discourse, and they perpetuate these harmful stereotypes and form political opinions.

I say “form” political opinions, but this is not quite the correct term. We live in filter bubbles and social media echo chambers that are genuinely difficult to break out of if we want to encounter perspectives other than our own mirrored back at us. Memes circulate within these bubbles and rarely pass through these filters. As such, they often do not “form” our opinions so much as they reflect and amplify them. This means that memes like these are genuinely dangerous because they are so insular and polarizing—they not only actively spread disinformation, but they revel in doing so. Through viewing these memes as an “insider,” or as someone who already supports their message, the viewer is less likely to consider differing opinions or, in some cases, even facts. The more often the viewer sees these kinds of memes, the less likely they are to be open to democratic discourse or civil debate. Therein lies a major problem: how can we have civil dialogue if the memes we encounter daily only reinforce the beliefs we already have? Next, I will show three types of Clinton memes that focus on her intelligence, Bill’s infidelity, and conspiracy theories and highlight how they functioned to spread disinformation.

I say “form” political opinions, but this is not quite the correct term. We live in filter bubbles and social media echo chambers that are genuinely difficult to break out of if we want to encounter perspectives other than our own mirrored back at us. Memes circulate within these bubbles and rarely pass through these filters. As such, they often do not “form” our opinions so much as they reflect and amplify them. This means that memes like these are genuinely dangerous because they are so insular and polarizing—they not only actively spread disinformation, but they revel in doing so. Through viewing these memes as an “insider,” or as someone who already supports their message, the viewer is less likely to consider differing opinions or, in some cases, even facts. The more often the viewer sees these kinds of memes, the less likely they are to be open to democratic discourse or civil debate. Therein lies a major problem: how can we have civil dialogue if the memes we encounter daily only reinforce the beliefs we already have? Next, I will show three types of Clinton memes that focus on her intelligence, Bill’s infidelity, and conspiracy theories and highlight how they functioned to spread disinformation.

First, appearance. Clinton is an animated woman of many facial expressions, and memers love to choose photos of at awkward moments. The first is clearly photoshopped to make her look older, but the other two do not appear to be. Notably, the text fixates on her supporters, belittling their intelligence. The goal of these memes is twofold: to make fun of how Clinton looks and to call her and her supporters stupid. The humor here is rooted in demagoguery. As Patricia Roberts-Miller (2017) explains, “demagogic humor is generally mean, and doesn’t have the destabilizing effect that a lot of humor has (in which at least one part of the joke is on the person telling it)—it’s only about the out-group and their minions” (p. 100). These jokes quite frankly aren’t that funny, or at least not particularly clever. These memes are akin to middle school playground insults, and would likely only draw people with likeminded opinions. In other words, these memes were not meant to change anyone’s mind about Clinton, but only to reinforce the boundaries between those who like her and those who don’t.

The next set of Clinton memes is related to Bill’s infidelity. These two continue the trend of using photos of her at awkward moments, one going so far as to show her holding up two fingers which, in connection to the text, make it look like she is referencing the size of her husband’s genitalia. Both are also interesting cases of disinformation and distraction. They open with text that presents a real issue (gun control and Clinton’s emails) to something extra-contextual (Bill’s infidelity and a famous line from his trial). The inherent claim in each is that because of her husband’s infidelity, she is unfit to be president. To pro-Clinton viewers, the premises in each meme have no connection; but to anti-Clinton viewers, this is a powerful enthymeme with the unstated premise that any woman whose husband cheats on her is incapable of leading a country. Similarly, these memes provoke demagogic laughter while creating a narrative that, through repetition, creates a distraction from political issues. Mina (2019) explains that narratives like these “hold power in our minds. The more a meme sticks, the more likely the deeper narrative sticks in turn” (p. 117). Again, these memes are likely did not recruit new anti-Clinton support but instead solidified an already tightly held belief that Clinton was unfit to be president.

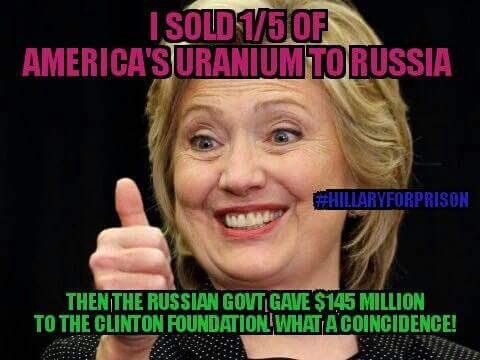

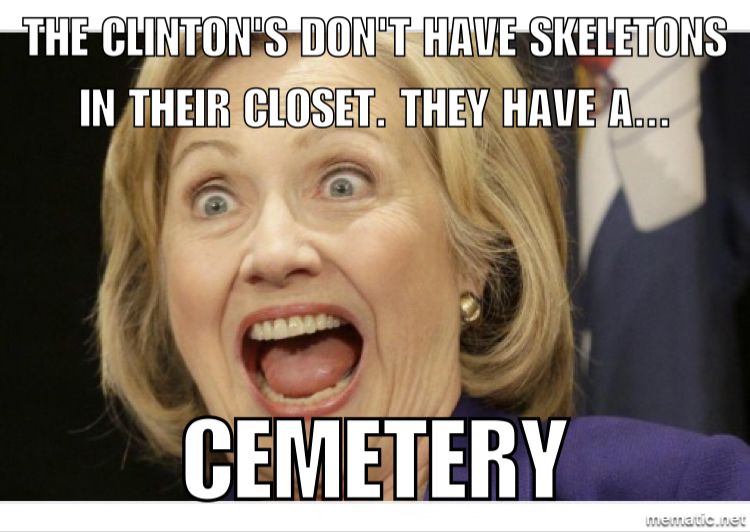

The final set of memes were especially useful disinformation tools: conspiracy theories. Since both cram a lot of text in one meme, I will show them separately before analyzing them together. First, the central figures of each meme continue to play on the trope of using awkward images of Clinton, the first with a smug expression giving a thumbs up, the second with one of her exaggerated laughs. Second, notice the conspiracy theories each perpetuates: the one on the right involves the Uranium one deal with Russia, which both PolitiFact and Snopes have denounced as false (Emery, 2017; Putterman, 2018); according to PolitiFact, a similar version of this meme that included Robert Mueller was recently circulated on Facebook in December 2018 and flagged by the platform’s newish “fake news” filter (Putterman, 2018). The meme on the left refers to the “body count” theory which claims that the Clintons have ordered the deaths of people who had incriminating evidence against them. This is an old theory, dating as far back as the 90s, but again, both PolitiFact and Snopes have also denounced these rumors as false, with PolitiFact going so far as to give this theory the “pants on fire” rating reserved for claims that have no verifying evidence to support them (Snopes Staff, 1998; Selby, 2017).

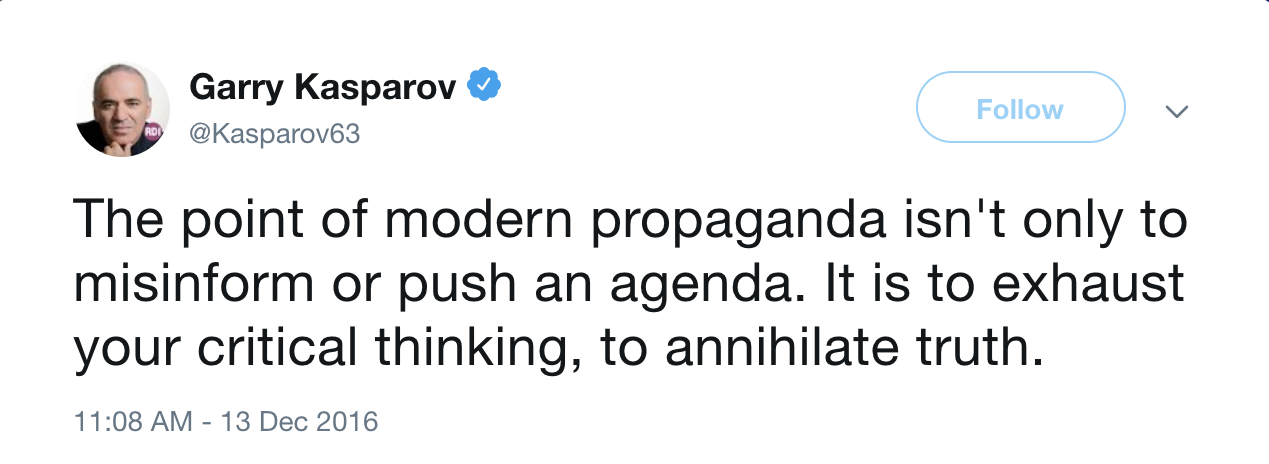

These memes serve as a form of modern-day propaganda. Older propaganda used to be one message that people either got behind or pretended to lest they suffer the consequences. But the rise of digital technologies makes it easier to create alternative narratives. As Russian chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov tweeted, “The point of modern propaganda isn’t only to misinform or push an agenda. It is to exhaust your critical thinking, to annihilate truth.” It is information overload that makes people less likely to fact-check and instead trust familiar sources of information rather than verifying for themselves. This is similar to what Alice was talking about yesterday, but kind of a new dimension: people are tired. They are exhausted and overwhelmed by disinformation.

These conspiracy theory memes function similarly. The two I show here represent only two of several theories. Notice, I didn’t even touch on the #PizzaGate conspiracy which resulted in a man shooting up a pizza place where supposedly Clinton and John Podesta were running a child pornography ring in the basement. But despite how unrealistic some of these conspiracy theories sound, they drown out verifiable information in a sea of disinformation. Anti-Clinton viewers of these memes likely did not research the conspiracy theories; or, what is more likely, any research they did ended when they encountered sources that did not match their worldview. As such, the memes’ connection between negative conspiracy theories and images that made Clinton look smug or like the stereotypical “hysterical woman” served to strengthen many anti-Clinton viewers’ perspectives that she is not only unfit to be president, but also downright evil.

These conspiracy theory memes function similarly. The two I show here represent only two of several theories. Notice, I didn’t even touch on the #PizzaGate conspiracy which resulted in a man shooting up a pizza place where supposedly Clinton and John Podesta were running a child pornography ring in the basement. But despite how unrealistic some of these conspiracy theories sound, they drown out verifiable information in a sea of disinformation. Anti-Clinton viewers of these memes likely did not research the conspiracy theories; or, what is more likely, any research they did ended when they encountered sources that did not match their worldview. As such, the memes’ connection between negative conspiracy theories and images that made Clinton look smug or like the stereotypical “hysterical woman” served to strengthen many anti-Clinton viewers’ perspectives that she is not only unfit to be president, but also downright evil.

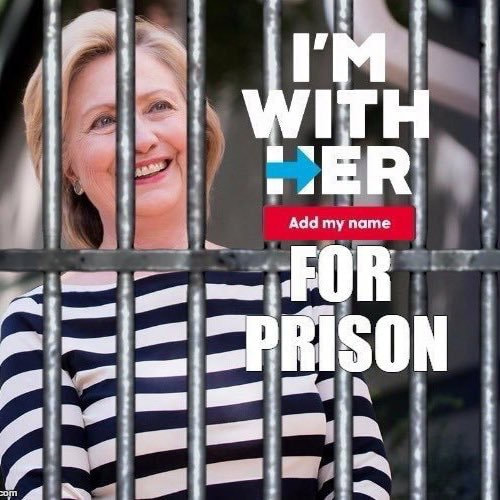

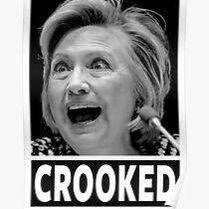

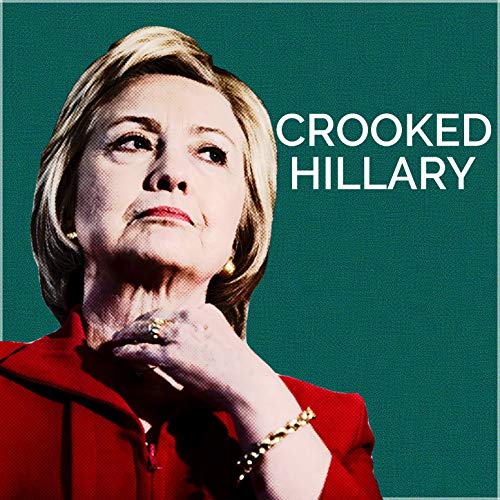

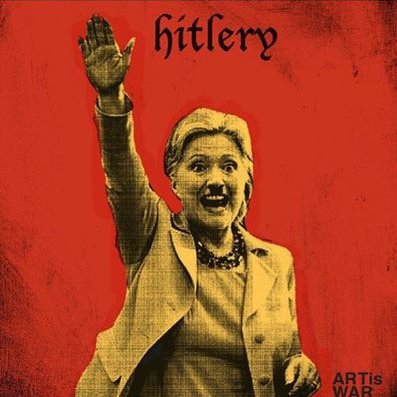

In this presentation, I’ve been focusing mainly on image macro memes that promoted disinformation during the 2016 election because they are easy to display and discuss in the conference presentation format. But there are also several analog memes that contributed to these disinformation efforts. During the campaign season, and one could easily argue even still today, Trump was a meme machine. In particular, the way he developed call-and-response tactics during his campaign speeches was reminiscent of the memetic behaviors I saw when I studied 4chan’s /b/ board where there seemed to be unwritten norms about how to respond when users say certain things. At certain points during his rallies, Trump would say something about Mexico, and his supporters would shout “build the wall.” Most relevant to this presentation, whenever he would mention Clinton, they would chant “lock her up.” This became a memetic rallying cry both at and beyond the rallies and it seeped its way into national narratives about Clinton that had little to do with the election. It was remixed to slogans like “Hillary for prison” and became buttons, tshirts, bumper stickers, and all manner of other analog memetic material. It has echoes in similar memes like calling Clinton “Crooked Hillary” and “Hitlery.”

And this meme has staying power. As recently as a few months ago, people are still saying “lock her up” about not only Clinton but other women who oppose Trump. Like the image macro memes I examined earlier, memetic chants like this one serve as demagogic propaganda that distracts and divides. Far from offering opportunities for dialog and debate, these memes only strengthen the in-groups while alienating the out-groups. They polarize and preclude the possibility of the two sides reconciling their perspectives and engaging in meaningful discussion. This is the issue at the core of political meming. Regardless of the memes’ potential to spread disinformation, which we know is something of which they are certainly capable, the larger problem comes from their ability to divide us.

I return now to the question I brought up near the beginning: how can we have civil dialogue if the memes we encounter daily only reinforce the beliefs we already have? Well, we can’t. So what do we do about it? This is a big question and it doesn’t have an easy answer, but I have two suggestions for today to get us started. The first is pedagogical. We should be teaching and talking about memes in our classes. It is our ethical obligation to help students become “good digital citizens” by addressing technological literacy and its link to citizenship and democracy. As Cindy Selfe (1999) has explained, this technological literacy means we have to be able to think critically about the media we consume and produce, we need to be able to take informed positions on complex issues, and we need to be able to listen—and listen rhetorically via Krista Ratcliffe (2005)—to opposing viewpoints, and we need to be able to do all of this in a variety of digital spaces across a range of media. Through looking at this small sampling of how memes can be used as dangerous political tools, it becomes clear that this technological literacy must include memes.

In addition, this technological literacy must include circulation practices. It’s one thing to create a meme and post it in a space where it will circulate briefly around a few users; it’s another when a meme goes viral and breaks out of its initial community. As such, teaching students about concepts like Jim Ridolfo and Danielle DeVoss’s (2009) rhetorical velocity is key. In addition, as Brandy Dieterle, Dustin Edwards, and Dan Martin (forthcoming, 2019) argue, users need to be critical of their own circulation practices. When a user reshares or retweets content, such as memes, they serve as another cog in a machine that perpetuates it. Regardless of if they add critical commentary or not, reshared memes can reinforce disinformation by keeping the content in circulation. The irony is not lost on me that even in this academic context I am doing exactly this by displaying the memes about which I speak, but I am also doing so critically to help us understand the shape of the problem.

This brings me to my second suggestion. We need to be critical of the content we show and share in our academic contexts. This is an especially pressing concern in digital aggression studies, where we question—or at least, should question—whether we will show screencaps or provide direct quotes of aggressive content, or if we will summarize it. The same goes for these memes. I’m not saying don’t show them; I’m saying do so intentionally and have a good reason for it. I ultimately decided to show them because Clinton’s appearance and specific gestures are essential to the analysis. But if all I needed was the text, I may have reconsidered. In addition, those of us who are content producers need to be aware of and critical of what we make and how we circulate it. And as Ryan pointed out yesterday, we especially need to be aware of Poe’s Law of the internet and that irony can come across as sincerity in certain contexts.

We’ve been slow to catch up with the pervasiveness of memetic media, in large part because we didn’t really take it seriously at first. We saw memes as mundane texts with little bearing on the “real world.” The case study here provides a glimpse of what we can learn from studying political memes. Some future research directions I’m looking into involve looking more closely at how different spots on the political spectrum fundamentally seem to disagree on what a meme looks like or how it functions. So not only are we not seeing each other’s memes because of filter bubbles, but we don’t even agree on the basic genre of a meme. More work is needed to fully understand what memes are capable of and how instrumental they are in polarizing political parties, especially at a time when everyone needs to be listening and learning.

In addition, this technological literacy must include circulation practices. It’s one thing to create a meme and post it in a space where it will circulate briefly around a few users; it’s another when a meme goes viral and breaks out of its initial community. As such, teaching students about concepts like Jim Ridolfo and Danielle DeVoss’s (2009) rhetorical velocity is key. In addition, as Brandy Dieterle, Dustin Edwards, and Dan Martin (forthcoming, 2019) argue, users need to be critical of their own circulation practices. When a user reshares or retweets content, such as memes, they serve as another cog in a machine that perpetuates it. Regardless of if they add critical commentary or not, reshared memes can reinforce disinformation by keeping the content in circulation. The irony is not lost on me that even in this academic context I am doing exactly this by displaying the memes about which I speak, but I am also doing so critically to help us understand the shape of the problem.

This brings me to my second suggestion. We need to be critical of the content we show and share in our academic contexts. This is an especially pressing concern in digital aggression studies, where we question—or at least, should question—whether we will show screencaps or provide direct quotes of aggressive content, or if we will summarize it. The same goes for these memes. I’m not saying don’t show them; I’m saying do so intentionally and have a good reason for it. I ultimately decided to show them because Clinton’s appearance and specific gestures are essential to the analysis. But if all I needed was the text, I may have reconsidered. In addition, those of us who are content producers need to be aware of and critical of what we make and how we circulate it. And as Ryan pointed out yesterday, we especially need to be aware of Poe’s Law of the internet and that irony can come across as sincerity in certain contexts.

We’ve been slow to catch up with the pervasiveness of memetic media, in large part because we didn’t really take it seriously at first. We saw memes as mundane texts with little bearing on the “real world.” The case study here provides a glimpse of what we can learn from studying political memes. Some future research directions I’m looking into involve looking more closely at how different spots on the political spectrum fundamentally seem to disagree on what a meme looks like or how it functions. So not only are we not seeing each other’s memes because of filter bubbles, but we don’t even agree on the basic genre of a meme. More work is needed to fully understand what memes are capable of and how instrumental they are in polarizing political parties, especially at a time when everyone needs to be listening and learning.

References

Dawkins, R. (1976). The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dieterle, B., Edwards, D., & Martin, P.D. (forthcoming, 2019). Confronting digital aggression with an ethics of circulation. In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital ethics: Rhetoric and responsibility in online aggression. New York: Routledge.

Emery, D. (2017, November 16). Hillary Clinton gave 20 percent of United States’ uranium to Russia in exchange for Clinton Foundation donations? Snopes. Retrieved from https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/hillary-clinton-uranium-russia-deal/

Kasparov, G [@Kasparov63]. (2016, December 13). The point of modern propaganda… [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/Kasparov63/status/808750564284702720

Marwick, A. (2019). “Beyond the Magic Bullet of Fake News: Disinformation as Identity Expression.” Paper given at Digital rhetoric/digital media in the post-truth age. Tuscaloosa, AL.

Milner, R. (2013). Pop polyvocality: Internet memes, public participation, and the Occupy Wall Street movement. International Journal of Communication, 7, 2357-2390.

Mina, A. X. (2019). Memes to movements: How the world’s most viral media is changing social protest and power. Boston: Beacon Press.

Putterman, S. (2018, Dec 7). Complex tale involving Hillary Clinton, uranium and Russia resurfaces. PolitiFact. Retrieved from https://www.politifact.com/facebook-fact-checks/statements/2018/dec/07/blog-posting/complex-tale-involving-hillary-clinton-uranium-rus/

Ratcliffe, K. (2005). Rhetorical listening: Identification, gender, whiteness. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois Unviersity Press.

Ridolfo, J & DeVoss, D. (2009). Composing for recomposition: Rhetorical velocity and delivery. Kairos, 13(2).

Roberts-Miller, P. (2017). Demagoguery and democracy. New York, NY: The Experiment.

Snopes Staff. (1998, January 24). Clinton Body Bags. Snopes. Retreived from https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/clinton-body-bags/

Selby, W. G. (2017, July 5). Pete Olson said Bill Clinton basically told Loretta Lynch ‘we killed Vince Foster.’ PolitiFact. Retrieved from https://www.politifact.com/texas/statements/2017/jul/05/pete-olson/pete-olson-said-bill-clinton-basically-told-lorett/

Selfe, C. L. (1999). Technology and literacy in the twenty-first century. Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press.

Shepherd, R. (2019). “Gaming reddit: r/thedonald and the 2016 presidential election.” Paper given at Digital rhetoric/digital media in the post-truth age. Tuscaloosa, AL.

Sparby, E. M. (2017a). Memes and 4chan and haters, oh my! Rhetoric, identity, and online aggression (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest.

Sparby, E. M. (2017b). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric in 4chan’s collective identity. Computers and Composition, 45, pp. 85-97.

Vie, S. (2014). In defense of ‘slacktivism’: The Human Rights Campaign Facebook logo as digital activism. First Monday, 19(4). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/article/view/4961/3868

Dieterle, B., Edwards, D., & Martin, P.D. (forthcoming, 2019). Confronting digital aggression with an ethics of circulation. In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital ethics: Rhetoric and responsibility in online aggression. New York: Routledge.

Emery, D. (2017, November 16). Hillary Clinton gave 20 percent of United States’ uranium to Russia in exchange for Clinton Foundation donations? Snopes. Retrieved from https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/hillary-clinton-uranium-russia-deal/

Kasparov, G [@Kasparov63]. (2016, December 13). The point of modern propaganda… [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/Kasparov63/status/808750564284702720

Marwick, A. (2019). “Beyond the Magic Bullet of Fake News: Disinformation as Identity Expression.” Paper given at Digital rhetoric/digital media in the post-truth age. Tuscaloosa, AL.

Milner, R. (2013). Pop polyvocality: Internet memes, public participation, and the Occupy Wall Street movement. International Journal of Communication, 7, 2357-2390.

Mina, A. X. (2019). Memes to movements: How the world’s most viral media is changing social protest and power. Boston: Beacon Press.

Putterman, S. (2018, Dec 7). Complex tale involving Hillary Clinton, uranium and Russia resurfaces. PolitiFact. Retrieved from https://www.politifact.com/facebook-fact-checks/statements/2018/dec/07/blog-posting/complex-tale-involving-hillary-clinton-uranium-rus/

Ratcliffe, K. (2005). Rhetorical listening: Identification, gender, whiteness. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois Unviersity Press.

Ridolfo, J & DeVoss, D. (2009). Composing for recomposition: Rhetorical velocity and delivery. Kairos, 13(2).

Roberts-Miller, P. (2017). Demagoguery and democracy. New York, NY: The Experiment.

Snopes Staff. (1998, January 24). Clinton Body Bags. Snopes. Retreived from https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/clinton-body-bags/

Selby, W. G. (2017, July 5). Pete Olson said Bill Clinton basically told Loretta Lynch ‘we killed Vince Foster.’ PolitiFact. Retrieved from https://www.politifact.com/texas/statements/2017/jul/05/pete-olson/pete-olson-said-bill-clinton-basically-told-lorett/

Selfe, C. L. (1999). Technology and literacy in the twenty-first century. Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press.

Shepherd, R. (2019). “Gaming reddit: r/thedonald and the 2016 presidential election.” Paper given at Digital rhetoric/digital media in the post-truth age. Tuscaloosa, AL.

Sparby, E. M. (2017a). Memes and 4chan and haters, oh my! Rhetoric, identity, and online aggression (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest.

Sparby, E. M. (2017b). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric in 4chan’s collective identity. Computers and Composition, 45, pp. 85-97.

Vie, S. (2014). In defense of ‘slacktivism’: The Human Rights Campaign Facebook logo as digital activism. First Monday, 19(4). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/article/view/4961/3868