© Erika M. Sparby

Toward an Ethic of Self-Care and Protection When Researching Digital Aggression

Adapted from a presentation at Computers and Writing 2019

|

Digital aggression studies is a relatively new endeavor, and one of the downsides to this newer area of inquiry is that not many people have talked about how they do it, including the research methods and methodologies needed to carry out effective research. In summer 2015, I collected data from the /b/ board on 4chan for a study of how and why digital aggression flourishes in anonymous spaces, but I’ll be honest I had no idea what I was doing. I mistakenly thought I would be able to adapt digital methods and methodologies to my study without modification. However, it turns out that this was not the case. In addition, I was naïve about how protected I would be as an academic researcher.

|

And so, in this presentation I posit an ethic of self-care and protection when studying digital aggression. I build this methodology off of Gesa Kirsch and Jacqueline Royster’s (1995) discussion of an ethic of care. Drawing from previous scholarship, they explain that an ethic of care “must be guided by natural sentiment” and that it “requires one to place herself in an empathetic relationship in order to understand the other’s point of view” (p. 21). However, they point out that an ethic of care also requires researchers to be deeply attuned to their own positions of power and to be willing “to open themselves to change and learning, to reinterpreting their own lives” (p. 22). Similarly, an ethic of self-care and protection requires researchers to tune into themselves and their needs during the process of research and adapt to new developments as it progresses. In addition, it requires researchers to be ultra-aware of the rhetorical velocity of their work and digital identities post-publication. First, I’ll talk about the self-care part of this ethic in more detail. For me this mostly meant lengthening my research timeline to account for more breaks and off-days during the study so that I could recover from the exhaustion and emotional distress that spending so much time in a hostile forum could cause. Let me illustrate this with a couple of examples from my 4chan study.

First example. I was relatively early in my data collection and was planning on spending at least 3 hours a day collecting data from various threads. I’d been on 4chan quite a bit in my misspent youth, but either I’d forgotten how bad it could be or it really had gotten worse over the decade or so since I’d last visited. I’d forgotten about gore porn. The purpose of gore porn is to shock or offend viewers by posting the most outrageous and gruesome content depicting images and videos of people dying or being killed, being beaten, or suffering extreme bodily injuries. As you can imagine, encountering this kind of content was horrifying. I’ve seen things that continue to haunt me. As the study went on, I got better at recognizing and avoiding gore porn, but even still, encountering it was an inevitable part of the study.

Second example. 4chan is notoriously anti-woman. If a woman wants to self-identify in the forum, she’s met with the phrase “tits or gtfo,” which means “show your breasts to prove that you’re a woman or leave the site.” Posts about women are full of vitriol and misogynistic language. Pornographic images, including creepshots, sleepshots (images taken of women’s bodies without their knowledge or while they’re sleeping), and other nonconsensual images show up frequently. Sometimes images of women who have been beaten appear. I knew all this going in, but after a few weeks of spending time in this space, I was exhausted and dispirited. This was a space that seemed to be against the very notion that I might even be a human—even if only ironically—let alone that I should be allowed to research them. I’m not the only researcher of hostile spaces who has felt this way.

Gruwell recounts her experiences researching hostile spaces in a way that summarizes exactly how I felt: “Most research is draining in one respect or another, but there was something especially taxing about intentionally reading content meant to silence women like me—feminists committed to identifying and resisting sexism, racism, and homophobia online (p. 92).

This is just a brief snapshot from my own experiences of what researching a hostile digital space can look like, and everyone’s experience is undoubtedly different. But here’s what I wish I had done. I wish I had paid attention to my own needs and mental health and taken some breaks when I needed to. This is something an ethic of self-care and protection can reinforce. Ultimately, it’s up to the individual researcher to decide to take breaks and consciously heal from exposure to these spaces, but the pressures of academia often make us feel like we can’t. An ethic of self-care and protection gives us permission to step away. It reminds us to put our health at the forefront.

This methodology also includes protection before and after publication. It is no secret that those who study or remark on hostile digital spaces often become the targets of aggression. Nowhere has this been demonstrated more acutely than in GamerGate, the targeted harassment of woman video game figures in 2014. In particular, two of the targets—Anita Sarkeesian and Felicia Day—made the list of targets specifically because of their critiques. For Sarkeesian, her video series through Feminist Frequency called Tropes Vs. Women in Video Games, which analyzed video games through a feminist lens, earned her a top spot on the list of targets. For Day, it was a comment on Twitter during the attacks about how they were making her nervous that resulted in her being doxxed the next day. Even in academia, scholars who address digital aggression face backlash, such as our own panelist Leigh Gruwell details. In addition, a quick glance at some of the older posts on Whitney Phillips’s blog (author of This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things (2015), which connects 4chan trolling to mainstream culture) shows that aggressors will find researchers in digital spaces and use their tactics on them to try to discredit, harass, and abuse them. Vyshali Manivannan (2019) also recounts a time when 4chan discussed her article in ways that could have spilled over into harassment but thankfully did not. Notice that all of the people I’ve listed here are women. More on that in a moment.

As such, when we are preparing our manuscripts for publication, we need to have a heightened awareness of the rhetorical velocity of our work, or for where our work will be shared and reshared and who will have access to it beyond our typical academic audience. Most scholars can publish an article or a book without such careful consideration of who will read it outside of the field. In fact, with the rise of open access, some scholars are actively seeking to publish in spaces where the public could have easy access to their work. As someone who studies digital aggression, I am conflicted. On the one hand, I want my work to be available to anyone who is interested, but on the other hand, I don’t want the communities I study to find me. As such, we need to make careful considerations about how and where we publish our work. Allow me to illustrate with two examples.

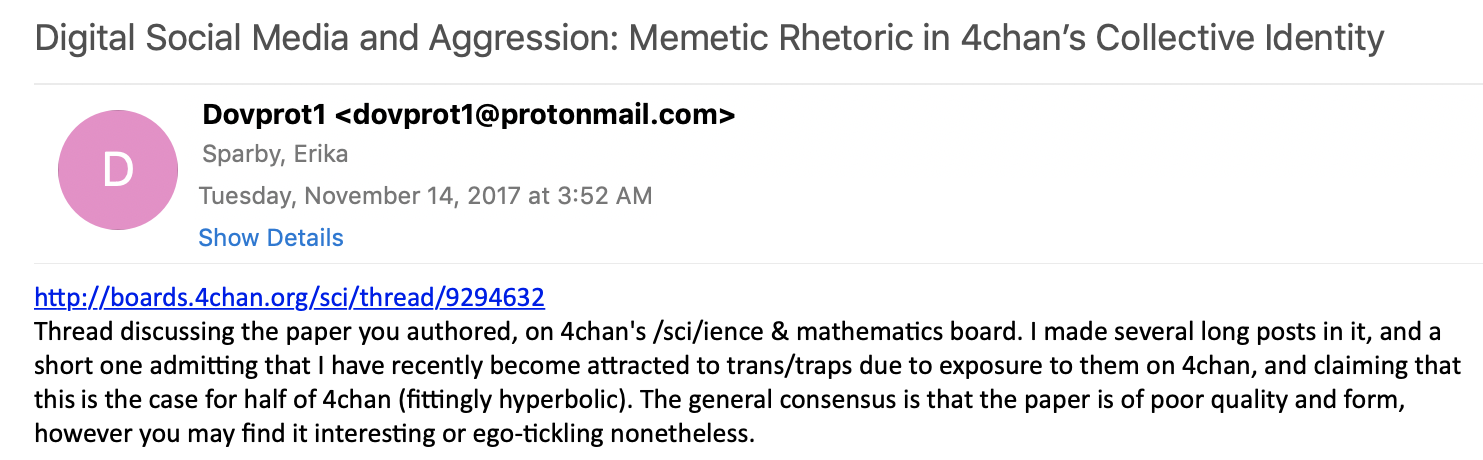

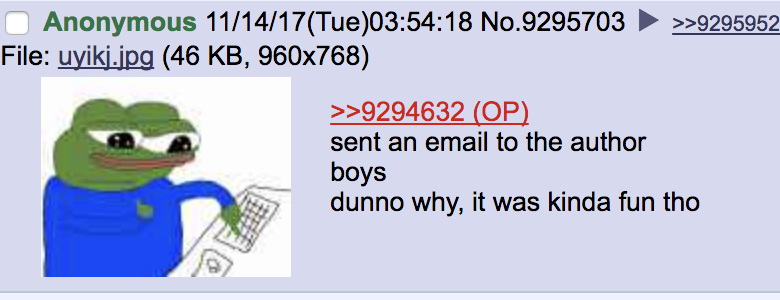

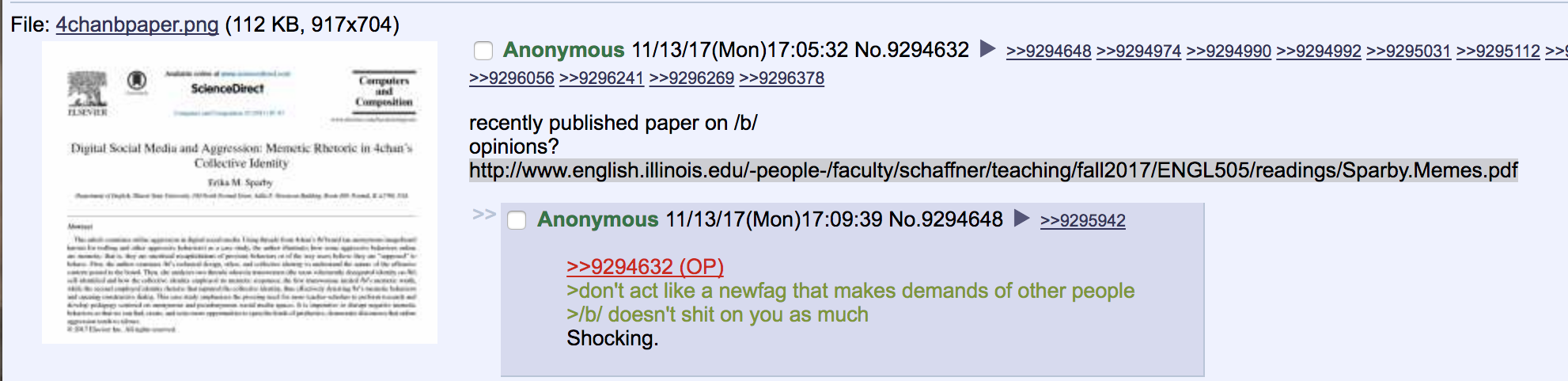

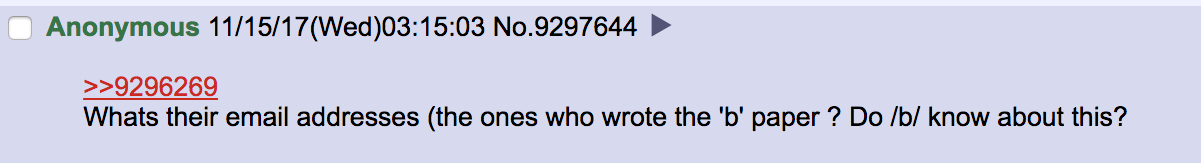

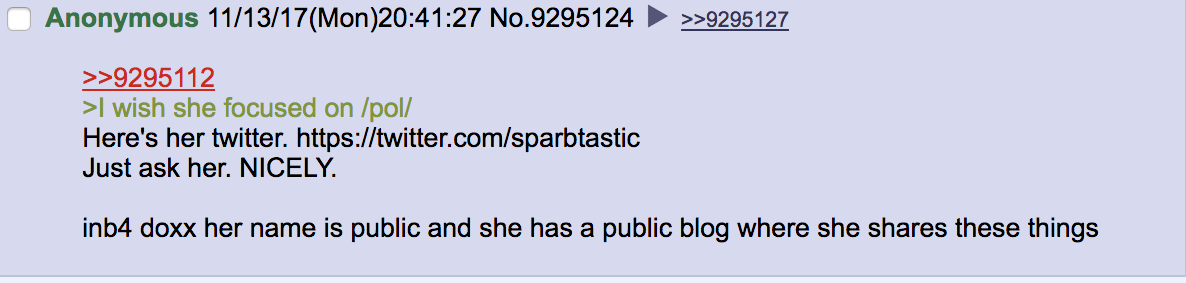

First example. In September 2017 I published an article about my 4chan study in Computers and Composition. In mid-November, I received an email from an anonymous burner account letting me know that it was being discussed on /sci/, a lesser known forum on 4chan. And he was proud of it too, boasting about it in the forum. I immediately found the thread and read it. I had intentionally chosen Computers and Composition as a venue for my article because it was behind a paywall and I knew it would be more difficult for aggressors to find. But a well-meaning colleague at another university assigned my article in his graduate digital rhetoric course and linked the pdf on his publicly accessible course website. He took it down later when I emailed and asked him to. I have no idea if the original poster was a student in his course or if they found it some other way, but all it took was this one little paywall breach to make my article accessible to the community I most didn’t want to access it. Once /sci/ got their hands on the article, they attempted to discredit it (proving my article’s argument right in the process) and insult me. At one point someone talked about posting it to /b/, a much more active central hub of 4chan and the space I had studied; another poster briefly mentioned doxxing me. It was a tense few days before the thread fell inactive and slipped from the main board.

First example. I was relatively early in my data collection and was planning on spending at least 3 hours a day collecting data from various threads. I’d been on 4chan quite a bit in my misspent youth, but either I’d forgotten how bad it could be or it really had gotten worse over the decade or so since I’d last visited. I’d forgotten about gore porn. The purpose of gore porn is to shock or offend viewers by posting the most outrageous and gruesome content depicting images and videos of people dying or being killed, being beaten, or suffering extreme bodily injuries. As you can imagine, encountering this kind of content was horrifying. I’ve seen things that continue to haunt me. As the study went on, I got better at recognizing and avoiding gore porn, but even still, encountering it was an inevitable part of the study.

Second example. 4chan is notoriously anti-woman. If a woman wants to self-identify in the forum, she’s met with the phrase “tits or gtfo,” which means “show your breasts to prove that you’re a woman or leave the site.” Posts about women are full of vitriol and misogynistic language. Pornographic images, including creepshots, sleepshots (images taken of women’s bodies without their knowledge or while they’re sleeping), and other nonconsensual images show up frequently. Sometimes images of women who have been beaten appear. I knew all this going in, but after a few weeks of spending time in this space, I was exhausted and dispirited. This was a space that seemed to be against the very notion that I might even be a human—even if only ironically—let alone that I should be allowed to research them. I’m not the only researcher of hostile spaces who has felt this way.

Gruwell recounts her experiences researching hostile spaces in a way that summarizes exactly how I felt: “Most research is draining in one respect or another, but there was something especially taxing about intentionally reading content meant to silence women like me—feminists committed to identifying and resisting sexism, racism, and homophobia online (p. 92).

This is just a brief snapshot from my own experiences of what researching a hostile digital space can look like, and everyone’s experience is undoubtedly different. But here’s what I wish I had done. I wish I had paid attention to my own needs and mental health and taken some breaks when I needed to. This is something an ethic of self-care and protection can reinforce. Ultimately, it’s up to the individual researcher to decide to take breaks and consciously heal from exposure to these spaces, but the pressures of academia often make us feel like we can’t. An ethic of self-care and protection gives us permission to step away. It reminds us to put our health at the forefront.

This methodology also includes protection before and after publication. It is no secret that those who study or remark on hostile digital spaces often become the targets of aggression. Nowhere has this been demonstrated more acutely than in GamerGate, the targeted harassment of woman video game figures in 2014. In particular, two of the targets—Anita Sarkeesian and Felicia Day—made the list of targets specifically because of their critiques. For Sarkeesian, her video series through Feminist Frequency called Tropes Vs. Women in Video Games, which analyzed video games through a feminist lens, earned her a top spot on the list of targets. For Day, it was a comment on Twitter during the attacks about how they were making her nervous that resulted in her being doxxed the next day. Even in academia, scholars who address digital aggression face backlash, such as our own panelist Leigh Gruwell details. In addition, a quick glance at some of the older posts on Whitney Phillips’s blog (author of This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things (2015), which connects 4chan trolling to mainstream culture) shows that aggressors will find researchers in digital spaces and use their tactics on them to try to discredit, harass, and abuse them. Vyshali Manivannan (2019) also recounts a time when 4chan discussed her article in ways that could have spilled over into harassment but thankfully did not. Notice that all of the people I’ve listed here are women. More on that in a moment.

As such, when we are preparing our manuscripts for publication, we need to have a heightened awareness of the rhetorical velocity of our work, or for where our work will be shared and reshared and who will have access to it beyond our typical academic audience. Most scholars can publish an article or a book without such careful consideration of who will read it outside of the field. In fact, with the rise of open access, some scholars are actively seeking to publish in spaces where the public could have easy access to their work. As someone who studies digital aggression, I am conflicted. On the one hand, I want my work to be available to anyone who is interested, but on the other hand, I don’t want the communities I study to find me. As such, we need to make careful considerations about how and where we publish our work. Allow me to illustrate with two examples.

First example. In September 2017 I published an article about my 4chan study in Computers and Composition. In mid-November, I received an email from an anonymous burner account letting me know that it was being discussed on /sci/, a lesser known forum on 4chan. And he was proud of it too, boasting about it in the forum. I immediately found the thread and read it. I had intentionally chosen Computers and Composition as a venue for my article because it was behind a paywall and I knew it would be more difficult for aggressors to find. But a well-meaning colleague at another university assigned my article in his graduate digital rhetoric course and linked the pdf on his publicly accessible course website. He took it down later when I emailed and asked him to. I have no idea if the original poster was a student in his course or if they found it some other way, but all it took was this one little paywall breach to make my article accessible to the community I most didn’t want to access it. Once /sci/ got their hands on the article, they attempted to discredit it (proving my article’s argument right in the process) and insult me. At one point someone talked about posting it to /b/, a much more active central hub of 4chan and the space I had studied; another poster briefly mentioned doxxing me. It was a tense few days before the thread fell inactive and slipped from the main board.

Second example. Jessica and I are currently finalizing our edited collection, Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression, and as part of our contract we negotiated to be able to release three chapters as open access on a personal website. But this also put us in a difficult position. [SLIDE 9] We wanted to be able to represent some of the awesome feminist work some of our authors did so we can offer a variety of work from the book, but doing so would put some authors—mostly women and a woman of color—at risk for being targeted by the communities that they studied. We ultimately decided on a chapter written by two white men and another written by two white men and a woman, although the latter is a bit precarious because it also talks about Milo Yiannopoulos, a former Breitbart writer and current alt-righter with a near cult-like following online.

|

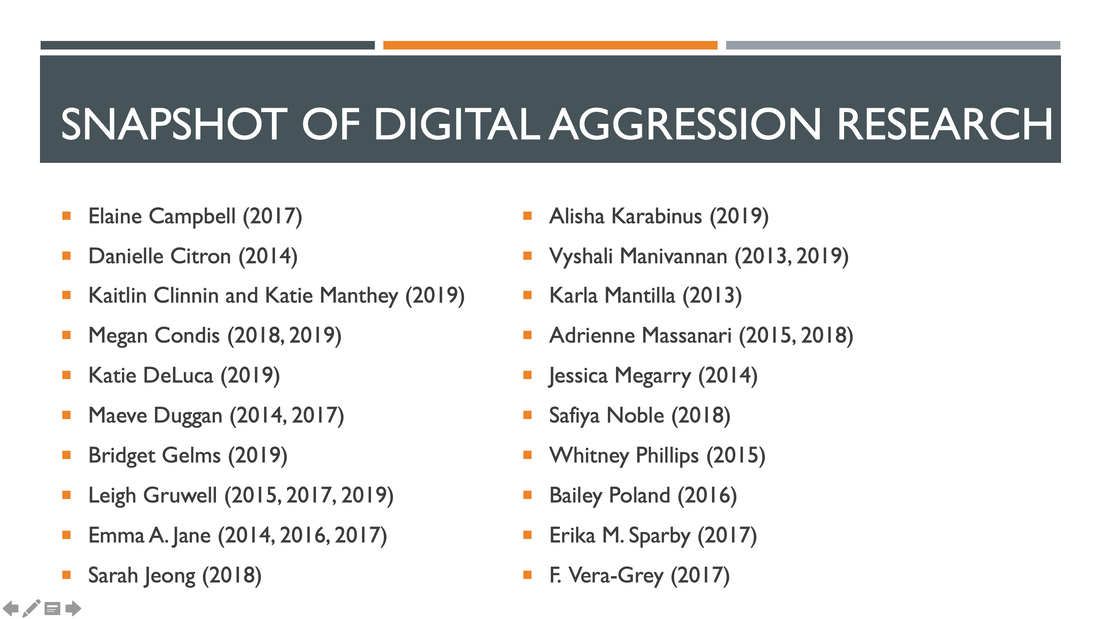

These examples show the need for careful consideration of the life of our scholarship post-publication. As I said earlier, this is a problem that uniquely affects women. This isn’t to say that men don’t also receive harassment for their work on digital aggression—they do, but not to the same extent as women. [SLIDE 10] And if you notice the names of the authors of work on aggression, it is mostly, although not exclusively, women. Here’s a quick snapshot of research by women across various fields since 2013.

|

But these examples highlight what Bridget Gelms (2019) calls “volatile visibility,” when women’s—especially women of color, queer women, and women with disabilities—very existence in digital spaces as active participants instead of passive observers makes them more likely to receive digital attacks. In addition, as women editors, we also recognized that anything that puts one of our authors in danger also puts us and the other authors in the collection in the same danger. Let that sink in for a second. We decided not to make certain important scholarship publicly available because it could negatively impact the careers of the author and everyone else involved in the project.

So in light of this volatile visibility, I think protecting ourselves as researchers is an ethical obligation. And ultimately, this is a small sampling of what digital aggression researchers are up against. We can’t just publish our work and move on to the next one. We have to think several steps ahead and deeply consider the rhetorical velocity of our work. What if I had published my 4chan article in one of our field’s open access journals, such as enculturation or Kairos, and users could have passed around a link to the full text? Would this added visibility have made me more vulnerable to attack? Absolutely.

I’ve only just started fleshing out what an ethic of self-care and protection looks like and how to incorporate it as a research methodology, but here are a few key takeaways:

First, an ethic of self-care recognizes that hostile digital spaces can cause exhaustion and emotional distress. It gives the researcher permission to step away and regroup before continuing research. I think it’s up to the individual person what this looks like, but for me it was going for a run, practicing taekwondo, or playing video games.

Second, an ethic of self-care recognizes that personal safety is paramount. It urges researchers to lock down their digital identities and carefully consider the rhetorical velocity of their work post-publication. I’ve noticed an uptick in digital aggression researchers asking audiences at conferences to refrain from live-tweeting or using certain words and hashtags, so maybe we could add disclaimers to our scholarship requesting it not be posted publicly even for educational purposes. Another consideration, and something I touched on briefly here but that needs more attention, is doxxing. Digital aggression researchers risk being doxxed for their work, which means that we need to put our digital identities on lockdown. Pay attention to who is following you on Twitter and who you friend on Facebook, Snapchat, etc. Google yourself and go through the process of removing your information from the endless stream of websites that post it. And finally, here’s the shameless plug, get involved in the newly formed Digital Aggression Working Group, which is working on putting together a toolkit for us to use to protect ourselves and our identities when doing this research.

Most importantly, we need to build this ethic of self-care and protection into our research methodologies from the very beginning of a project. Undoubtedly, there are other aspects of this methodology that I have yet to uncover, but it’s a start. As I work toward drafting this into an article, I’m looking forward to any questions and feedback you may have.

So in light of this volatile visibility, I think protecting ourselves as researchers is an ethical obligation. And ultimately, this is a small sampling of what digital aggression researchers are up against. We can’t just publish our work and move on to the next one. We have to think several steps ahead and deeply consider the rhetorical velocity of our work. What if I had published my 4chan article in one of our field’s open access journals, such as enculturation or Kairos, and users could have passed around a link to the full text? Would this added visibility have made me more vulnerable to attack? Absolutely.

I’ve only just started fleshing out what an ethic of self-care and protection looks like and how to incorporate it as a research methodology, but here are a few key takeaways:

First, an ethic of self-care recognizes that hostile digital spaces can cause exhaustion and emotional distress. It gives the researcher permission to step away and regroup before continuing research. I think it’s up to the individual person what this looks like, but for me it was going for a run, practicing taekwondo, or playing video games.

Second, an ethic of self-care recognizes that personal safety is paramount. It urges researchers to lock down their digital identities and carefully consider the rhetorical velocity of their work post-publication. I’ve noticed an uptick in digital aggression researchers asking audiences at conferences to refrain from live-tweeting or using certain words and hashtags, so maybe we could add disclaimers to our scholarship requesting it not be posted publicly even for educational purposes. Another consideration, and something I touched on briefly here but that needs more attention, is doxxing. Digital aggression researchers risk being doxxed for their work, which means that we need to put our digital identities on lockdown. Pay attention to who is following you on Twitter and who you friend on Facebook, Snapchat, etc. Google yourself and go through the process of removing your information from the endless stream of websites that post it. And finally, here’s the shameless plug, get involved in the newly formed Digital Aggression Working Group, which is working on putting together a toolkit for us to use to protect ourselves and our identities when doing this research.

Most importantly, we need to build this ethic of self-care and protection into our research methodologies from the very beginning of a project. Undoubtedly, there are other aspects of this methodology that I have yet to uncover, but it’s a start. As I work toward drafting this into an article, I’m looking forward to any questions and feedback you may have.

References

Campbell, E. (2017). “Apparently being a self-obsessed c**t is now academically lauded”: Experiencing Twitter trolling of autoethnographers. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(3).

Citron, D. (2014). Hate crimes in cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clinnin, K. and Manthey, K. (2019). How not to be a troll: Practicing rhetorical technofeminism in online comments. Computers and Composition, in press.

Condis, M. (2018). Gaming masculinity: Trolls, fake geeks, and the gendered battle for online culture. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Condis, M. (2019). “Hateful Games: Why White Supremacist Recruiters Target Gamers and How to Stop Them.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

DeLuca, K. (2019). “Fostering Phronesis in Digital Rhetorics: Developing a Rhetorical and Ethical Approach to Online Engagements.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

Duggan, M. (2014). Online harassment. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/10/22/online-harassment/

Duggan, M. (2017). Online harassment 2017. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/07/11/online-harassment-2017/

Gelms, B. (2019). “Volatile Visibility: How Online Harassment Makes Women Disappear.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

Gruwell, L. (2015). Wikipedia’s politics of exclusion: Gender, epistemology, and feminist rhetorical (in)action. Computers and Composition, 37, 117-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2015.06.009

Gruwell, L. (2017). Writing against harassment: Public writing pedagogy and online hate. Composition Forum, 36. Retrieved from http://compositionforum.com/issue/36/against-harassment.php

Gruwell, L. (2019). “Feminist Research on the Toxic Web: The Ethics of Access, Affective Labor, and Harassment.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

Jane, E. A. (2014a). ‘Back to the kitchen, cunt’: Speaking the unspeakable about online misogyny. Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, 28(4), 558-570.

Jane, E. A. (2014b). ‘Your a ugly, whorish, Slut’: Understanding e-bile. Feminist Media Studies, 14(4), 531-546.

Jane, E. A. (2016). Online misogyny and feminist digilantism. Continuum, 30(3), 284–297.

Jane, E. (2017). Feminist digilante responses to a slut-shaming on Facebook. Social Media + Society, 3(2), 1-10.

Jeong, S. (2018). The Internet of garbage. Washington, DC: Vox Media.

Karabinus, A. (2019). “Theorycraft and Online Harassment: Mobilizing Status Quo Warriors.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

Kirsch, G E., & Ritchie, J. S. (1995). Beyond the personal: Theorizing a politics of location in composition research. College Composition and Communication, 46(1), 7-29.

Manivannan, V. (2013). Tits or GTFO: The logics of misogyny on 4chan’s Random - /b/. Fibreculture, 22. Retrieved from http://twentytwo.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-158-tits-or-gtfo-the-logics-of-misogyny-on-4chans-random-b/

Manivannan, V. (2019). “Maybe She can Be a Feminist and Still Claim her own Opinions? The Story of an Accidental Counter-Troll, A treatise in 9 movements.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

Mantilla, K. (2013). Gendertrolling: Misogyny adapts to new media. Feminist Studies, 39(2), 563–570.

Massanari, A. (2015). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329-346.

Massanari, A. L. (2018). Rethinking research ethics, power, and the risk of visibility in the era of the “alt-right” gaze. Social Media + Society, 4(2), 1-9.

Megarry, J. (2014). Online incivility or sexual harassment? Conceptualising women’s experiences in the digital age. Women’s Studies International Forum, 47, 46-55.

Noble, S. U. (2018) Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Phillips, W. (2015). This is why we can’t have nice things: Mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Poland, B. (2016). Haters: Harassment, abuse, and violence online. Lincoln: Potomac Books.

Sparby, E. M. (2017). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric in 4chan’s collective identity. Computers and Composition, 45, pp. 85-97.

Vera-Gray, F. (2017). ‘Talk about a cunt with too much idle time’: Trolling feminist research. Feminist Review, 115(1), 61-78.

Citron, D. (2014). Hate crimes in cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clinnin, K. and Manthey, K. (2019). How not to be a troll: Practicing rhetorical technofeminism in online comments. Computers and Composition, in press.

Condis, M. (2018). Gaming masculinity: Trolls, fake geeks, and the gendered battle for online culture. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Condis, M. (2019). “Hateful Games: Why White Supremacist Recruiters Target Gamers and How to Stop Them.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

DeLuca, K. (2019). “Fostering Phronesis in Digital Rhetorics: Developing a Rhetorical and Ethical Approach to Online Engagements.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

Duggan, M. (2014). Online harassment. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/10/22/online-harassment/

Duggan, M. (2017). Online harassment 2017. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/07/11/online-harassment-2017/

Gelms, B. (2019). “Volatile Visibility: How Online Harassment Makes Women Disappear.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

Gruwell, L. (2015). Wikipedia’s politics of exclusion: Gender, epistemology, and feminist rhetorical (in)action. Computers and Composition, 37, 117-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2015.06.009

Gruwell, L. (2017). Writing against harassment: Public writing pedagogy and online hate. Composition Forum, 36. Retrieved from http://compositionforum.com/issue/36/against-harassment.php

Gruwell, L. (2019). “Feminist Research on the Toxic Web: The Ethics of Access, Affective Labor, and Harassment.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

Jane, E. A. (2014a). ‘Back to the kitchen, cunt’: Speaking the unspeakable about online misogyny. Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, 28(4), 558-570.

Jane, E. A. (2014b). ‘Your a ugly, whorish, Slut’: Understanding e-bile. Feminist Media Studies, 14(4), 531-546.

Jane, E. A. (2016). Online misogyny and feminist digilantism. Continuum, 30(3), 284–297.

Jane, E. (2017). Feminist digilante responses to a slut-shaming on Facebook. Social Media + Society, 3(2), 1-10.

Jeong, S. (2018). The Internet of garbage. Washington, DC: Vox Media.

Karabinus, A. (2019). “Theorycraft and Online Harassment: Mobilizing Status Quo Warriors.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

Kirsch, G E., & Ritchie, J. S. (1995). Beyond the personal: Theorizing a politics of location in composition research. College Composition and Communication, 46(1), 7-29.

Manivannan, V. (2013). Tits or GTFO: The logics of misogyny on 4chan’s Random - /b/. Fibreculture, 22. Retrieved from http://twentytwo.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-158-tits-or-gtfo-the-logics-of-misogyny-on-4chans-random-b/

Manivannan, V. (2019). “Maybe She can Be a Feminist and Still Claim her own Opinions? The Story of an Accidental Counter-Troll, A treatise in 9 movements.” In J. Reyman and E. M. Sparby (eds.) Digital Ethics: Rhetoric and Responsibility in Online Aggression. New York: Routledge.

Mantilla, K. (2013). Gendertrolling: Misogyny adapts to new media. Feminist Studies, 39(2), 563–570.

Massanari, A. (2015). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329-346.

Massanari, A. L. (2018). Rethinking research ethics, power, and the risk of visibility in the era of the “alt-right” gaze. Social Media + Society, 4(2), 1-9.

Megarry, J. (2014). Online incivility or sexual harassment? Conceptualising women’s experiences in the digital age. Women’s Studies International Forum, 47, 46-55.

Noble, S. U. (2018) Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Phillips, W. (2015). This is why we can’t have nice things: Mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Poland, B. (2016). Haters: Harassment, abuse, and violence online. Lincoln: Potomac Books.

Sparby, E. M. (2017). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric in 4chan’s collective identity. Computers and Composition, 45, pp. 85-97.

Vera-Gray, F. (2017). ‘Talk about a cunt with too much idle time’: Trolling feminist research. Feminist Review, 115(1), 61-78.