© Erika M. Sparby

Toward a Theory of Digital Aggression and Memetic Screen

Adapted from a presentation at Computers and Writing 2019

Content warning! Aggressive content ahead!

|

Typically, when we think of memes we think of mundane media artifacts that attempt humor and circulate through social media. They are memetic because they present some variation of something that has come before. This can mean sharing an image, video, gif, or some other media that has undergone or has the potential to undergo some form of remix. But memes can also encompass behaviors.

|

These behavior memes are more complex, but are generally some iteration of repeated behaviors in a new context. For example, if I share a content meme on Facebook I’ve increased its circulation and reach. Simultaneously, because I often share memes on Facebook, and because Facebook’s algorithms provide me a new context every time I refresh it, I’ve engaged in a memetic behavior.

In “Digital Social Media and Aggression” I showed that many behaviors on 4chan, a hostile digital space, are memetic. In that article, I showed that when users want to rupture the memetic behavioral patterns of the collective identity, they need to mirror those behaviors. That is, they need to talk and behave like the collective. In this presentation, I want to expand on this idea by reinventing Kenneth Burke’s terministic screens to define what I saw and begin to make more sense of it for digital rhetorics and digital aggression studies. Burke explains that terministic screens are a set terms through which we perceive our reality. Each of us has our own set of terministic screens that help us decipher and construct the world around us by providing a lens through which we can interpret it.

In today’s technological moment, I posit that our screens go beyond the terministic; for many of us who spend substantial amounts of time in digital spaces (although I would also argue that this carries over to the real world, but that’s a conversation for another time), our screens can also be memetic. Memetic screens are the media we consume, produce, and circulate online, as well as the memetic behaviors that we use to construct our digital spaces.

Importantly these memetic screens are not just unique to individuals. When many users gather in the same space, they can develop collective memetic screens. I argue that deciphering an online community’s memetic screens can be key to deciphering their collective identity and thus to pinpointing the kinds of aggressive behaviors perpetuated there and possibly even the motivations behind them, which can help us work to reduce instances of digital aggression.

In today’s technological moment, I posit that our screens go beyond the terministic; for many of us who spend substantial amounts of time in digital spaces (although I would also argue that this carries over to the real world, but that’s a conversation for another time), our screens can also be memetic. Memetic screens are the media we consume, produce, and circulate online, as well as the memetic behaviors that we use to construct our digital spaces.

Importantly these memetic screens are not just unique to individuals. When many users gather in the same space, they can develop collective memetic screens. I argue that deciphering an online community’s memetic screens can be key to deciphering their collective identity and thus to pinpointing the kinds of aggressive behaviors perpetuated there and possibly even the motivations behind them, which can help us work to reduce instances of digital aggression.

|

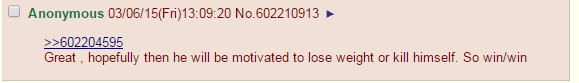

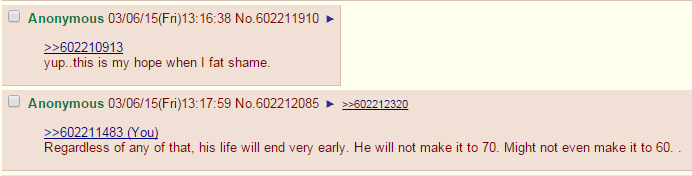

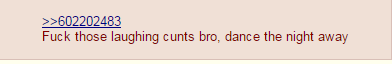

First, a brief example from about five years ago to show how I realized what memetic screens are and how they function. A quick look at the Dancing Man meme, a content meme that also involved collective memetic behaviors, briefly highlights some of these memetic screens. In March 2015, someone on 4chan posted an image of Sean O’Brien meant to fatshame and cyberbully him for dancing in public. The text states, “Spotted this specimen trying to dance the other week. He stopped when he saw us laughing.” The comments that followed in this thread continued in a similar line. Shortly after, a user created a new thread and reposted the image, but this time with a bolstering message and asking people to post and repost the phrase “fuck those laughing cunts bro, dance the night away,” thus creating an adjacent meme in the form of copypasta, or copy and pasted text. However, this thread had significantly fewer replies than the original, malicious one. 4chan’s behavior was cruel and malevolent. One of their memetic screens is shaming someone they perceive to be inferior.

|

Then, Dancing Man moved to reddit and popped up in a few different subreddits where his appearance revealed different memetic screens of different collectives there. On r/shit4chansays, it was, unsurprisingly, used similarly to 4chan, showing that this particular subreddit uses many of the same memetic screens as 4chan itself. But given the variety of subreddits available, it was inevitable that Dancing Man would appear in at least one of them in a variant form. In a body positivity subreddit, O’Brien’s image showed up with messages similar to the second 4chan thread, showing support for him, commiserating with him, and wishing him well. Here, users showed sympathy and empathy, revealing that one of their memetic screens involves dismantling hegemonic views of bodily perfection.

Next, Dancing Man reached Twitter when Cassandra Fairbanks posted the original image and text from 4chan to try to find him. Once O’Brien created a Twitter account and responded, Cassandra and over one-thousand other women threw him a celebrity-filled party to which he was the sole male invitee. From here, the meme made its way to Facebook as a Buzzfeed story and became a call to action against cyberbullying.The evolution of Dancing Man as it made its way to Facebook and Twitter reveals that a memetic screen determining behavior on both networks is social justice, although Twitter’s is more activist while Facebook’s trended more toward slacktivist.

Next, Dancing Man reached Twitter when Cassandra Fairbanks posted the original image and text from 4chan to try to find him. Once O’Brien created a Twitter account and responded, Cassandra and over one-thousand other women threw him a celebrity-filled party to which he was the sole male invitee. From here, the meme made its way to Facebook as a Buzzfeed story and became a call to action against cyberbullying.The evolution of Dancing Man as it made its way to Facebook and Twitter reveals that a memetic screen determining behavior on both networks is social justice, although Twitter’s is more activist while Facebook’s trended more toward slacktivist.

Ever since I watched Dancing Man go viral and then die out within about six months, I’ve been asking myself, what does it mean for digital rhetoric and digital aggression studies? This brief example shows that it is possible to learn a lot about a digital community in a short amount of time by examining the kinds of memes they circulate and the kinds of memetic behaviors they enable and encourage; in other words by determining the memetic screens that users call on to construct the world of their collective. So now I want to apply this theory to a more contemporary example: Facebook tag groups.

|

Essentially, Facebook tag groups are groups on Facebook meant mostly for tagging as text in replies to posts in other tag groups. Since many of these groups also encourage users to post memes or other approved content, they are a variant of Facebook meme groups. Here’s how they work. I’m in a group called “what object are we being compared to today, ladies?” which posts memes and screenshots that show men constructing elaborate metaphors comparing women to things like trash cans, cars, food, animals, and all other manner of objects.

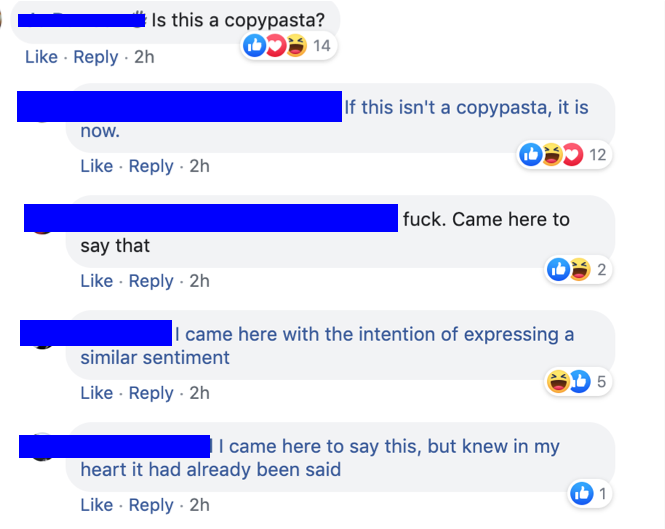

Last week, someone answered the filter questions with a bunch of anti-feminist vitriol full of misspellings, including of the “r-word.” I pointed out the misspelling, itself a memetic behavior across tag groups. In case it’s not clear, I do not support using the r-word. Online, it’s one of many commonly misspelled words that users point out by simply reposting the misspelled word. It’s a shaming mechanism for both the misspelling and for using the word to begin with. After I posted, someone responded with a hyperlinked phrase: “I came here to say this, but I knew in my heart it had already been said.” Since I was not yet a member of this group, I responded by linking to one I am a member of: “sounds like another fuckin group i gotta join but ok.” |

And that’s the end of our exchange, which consisted almost entirely of memetic behaviors: 1) the original screencap of the anti-feminist roast; 2) me pointing out the misspelling of a commonly misspelled word; 3) another group member and I responding with hyperlinked tag groups. All three of these behaviors are memetic screens, but only two of them are global across tag groups: making fun of the misspelling and responding with other tag groups. The first one, posting a screencap of answers to the filter questions when someone leaves unsavory answers, is common in this group, and may happen in other similar groups, but is not a global behavior across all tag groups. In addition, the guy’s anti-feminist rant on the filter questions is also an anti-memetic screen in this group. By identifying the defense of women’s humanity as a unique memetic screen, we can start identifying the kinds of behaviors the collective enables.

|

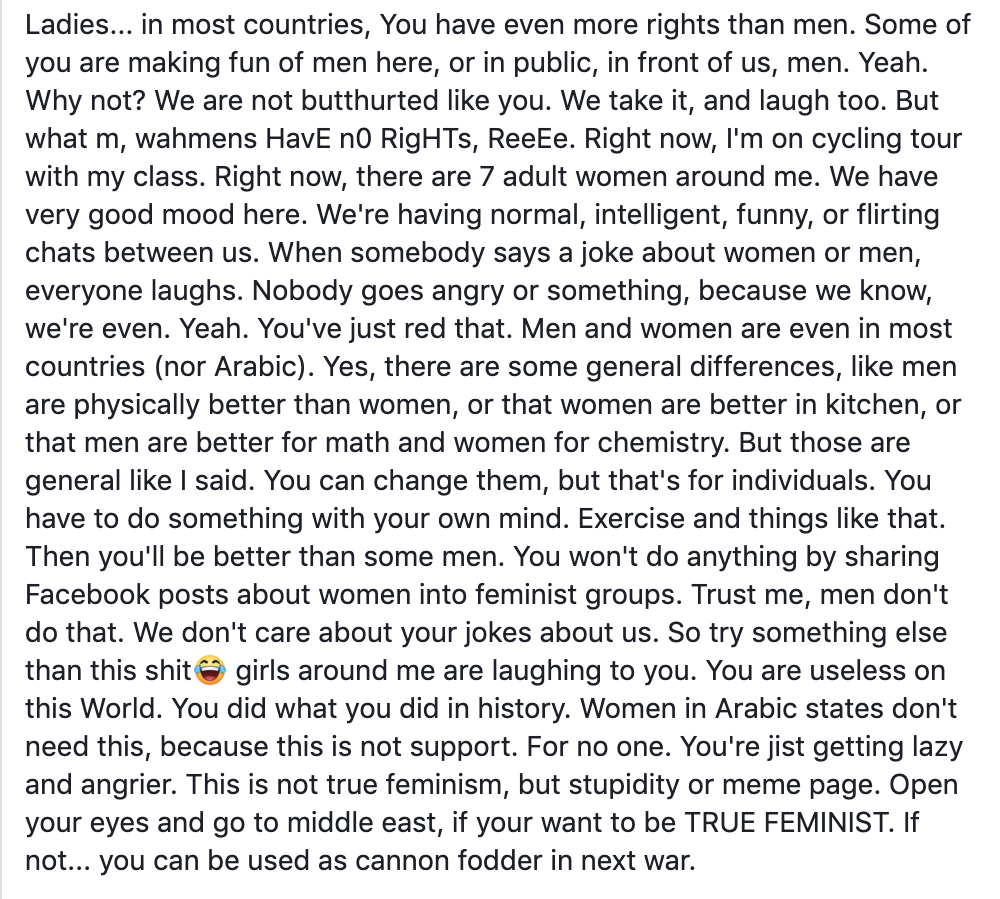

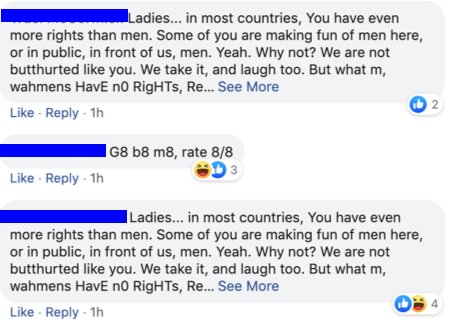

We don’t have to go much deeper into the group to see more memetic screens. A different guy posted about how women should just learn to be happy with what we have because we’re already equal and we just look silly for thinking we need more. There are a few different kinds of comments on this thread, and almost all of them are memetic.

|

First are ones referring to the post as copypasta. It seems likely that this paragraph was copied from another location and posted in the group ironically, but it’s not entirely clear.

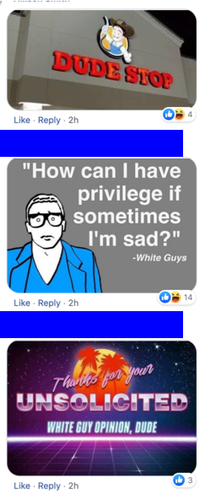

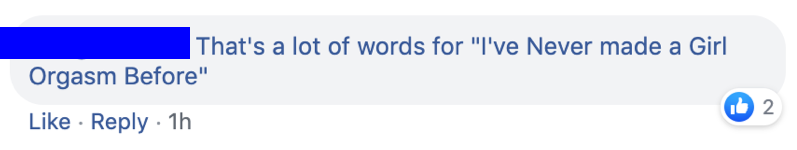

Another type of comment is images and memes ridiculing the OP, including a couple from me. This is also common behavior in tag groups when the OP says something distasteful, but the ones in this group and others like it tend to focus on the maleness of the original poster.

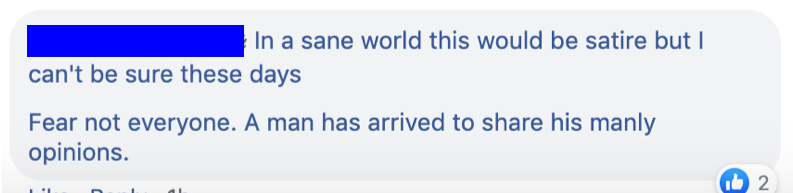

Finally, users also tag other groups in the comments, another common behavior in tag groups. However, along with the more general OP-bashing groups, such as “those certainly are all words” or “this made me say what so many times Macklemore is taking me thrift shopping,” most of the groups tagged are specific to this and similar groups, such as

- “I feel like men are not sending us their best people”

- “A white man with poor social awareness has an opinion, more at 11.”

- “Fear not everyone. A man has arrived to share his manly opinions.”

Together, these memetic behaviors, which are a response to a user posting an anti-memetic screen, point to and reinforce two memetic screens: 1) recognizing and valuing women’s humanity; 2) ridiculing anyone who is in denial of the need for feminism. These two memetic screens combine with others to drive community involvement.

This brief examination of two posts from “what object are we being compared to today, ladies?” reveals a couple important things. 1) Memetic screens dictate some core behaviors across Facebook tag groups; 2) certain groups have even more specific memetic screens relating to the kinds of content posted and groups tagged. This means that determining the memetic screens that drive a community can help users and researchers learn the behaviors of various collectives.

Now, “what object are we being compared to today, ladies?” is a relatively well-behaved group; as in, we don’t tend to post particularly aggressive content, although we definitely troll as both of these posts have shown. Following from Whitney Phillips, I draw a line between trolling and aggression, although the two terms are too often conflated. Trolling has come to signify all negative behaviors online, but actual trolling tends to be more playful and is not always negative. On the other hand, digital aggression tends to be more explicitly targeted at users based on their identities with the intent to harm and/or silence them. The OPs who deliberately posted anti-feminist content in an openly feminist group were aggressors. Those of us who replied to them were trolling. And in this case the trolling served to both critique the aggressors and model acceptable behaviors in the space. But without access to the community’s memetic screens, this differentiation would be more difficult to make.

For example, in the case of the first post, the OP is a moderator who posted a screencap of someone’s responses to the filter questions. Notice that she removed the user’s identifying information from the image, thus protecting his identity. If she had not, I would classify this as aggression because it could incite group members to contact this person and harass him. Because we don’t know who he is, he likely suffered no negative consequences aside from being disallowed entry to the group, which I would argue was never his goal to begin with. This kind of courtesy is not extended to all screencaps posted in all tag groups. This reveals another memetic screen of this group: protecting the privacy of all users, even those who actively engage in aggressive behaviors. In keeping with this memetic screen, I’ve also extended the same consideration to the screencaps I showed here, blocking out the names of posters.

So why do we need “memetic screens?” What benefit comes from giving these behaviors a name? These behaviors

Moving forward, I plan to research memetic screens in the context of more hostile spaces. For the most part, my tag groups are currently limited to LeftBook, meaning they are more liberal. Many have rules explicitly prohibiting racist, sexist, homophobic, and/or ableist content and behaviors and employ a team of volunteer admins and mods to ban users who violate them. But the thing about tag groups is, they’re hard to find unless you see them tagged. I’ve been intentionally falling down a rabbit hole of progressively more chaotic tag groups and have recently gained access to a couple that may eventually provide pathways to more hostile spaces.

Through studying memetic screens in conjunction with Facebook tag groups and online aggression, I hope to uncover more ways that both memetic content and behaviors enable or respond to aggressive behaviors. It seems that if you can figure out a space’s memetic screens, you can start to work against their aggressive behaviors by learning how to speak to them with the ethos of an insider.

This brief examination of two posts from “what object are we being compared to today, ladies?” reveals a couple important things. 1) Memetic screens dictate some core behaviors across Facebook tag groups; 2) certain groups have even more specific memetic screens relating to the kinds of content posted and groups tagged. This means that determining the memetic screens that drive a community can help users and researchers learn the behaviors of various collectives.

Now, “what object are we being compared to today, ladies?” is a relatively well-behaved group; as in, we don’t tend to post particularly aggressive content, although we definitely troll as both of these posts have shown. Following from Whitney Phillips, I draw a line between trolling and aggression, although the two terms are too often conflated. Trolling has come to signify all negative behaviors online, but actual trolling tends to be more playful and is not always negative. On the other hand, digital aggression tends to be more explicitly targeted at users based on their identities with the intent to harm and/or silence them. The OPs who deliberately posted anti-feminist content in an openly feminist group were aggressors. Those of us who replied to them were trolling. And in this case the trolling served to both critique the aggressors and model acceptable behaviors in the space. But without access to the community’s memetic screens, this differentiation would be more difficult to make.

For example, in the case of the first post, the OP is a moderator who posted a screencap of someone’s responses to the filter questions. Notice that she removed the user’s identifying information from the image, thus protecting his identity. If she had not, I would classify this as aggression because it could incite group members to contact this person and harass him. Because we don’t know who he is, he likely suffered no negative consequences aside from being disallowed entry to the group, which I would argue was never his goal to begin with. This kind of courtesy is not extended to all screencaps posted in all tag groups. This reveals another memetic screen of this group: protecting the privacy of all users, even those who actively engage in aggressive behaviors. In keeping with this memetic screen, I’ve also extended the same consideration to the screencaps I showed here, blocking out the names of posters.

So why do we need “memetic screens?” What benefit comes from giving these behaviors a name? These behaviors

- are often nearly automatic, and perhaps even uncritical;

- represent the in-jokes of a collective and help define their humor;

- model good and bad behavior within the collective and train users how to behave.

Moving forward, I plan to research memetic screens in the context of more hostile spaces. For the most part, my tag groups are currently limited to LeftBook, meaning they are more liberal. Many have rules explicitly prohibiting racist, sexist, homophobic, and/or ableist content and behaviors and employ a team of volunteer admins and mods to ban users who violate them. But the thing about tag groups is, they’re hard to find unless you see them tagged. I’ve been intentionally falling down a rabbit hole of progressively more chaotic tag groups and have recently gained access to a couple that may eventually provide pathways to more hostile spaces.

Through studying memetic screens in conjunction with Facebook tag groups and online aggression, I hope to uncover more ways that both memetic content and behaviors enable or respond to aggressive behaviors. It seems that if you can figure out a space’s memetic screens, you can start to work against their aggressive behaviors by learning how to speak to them with the ethos of an insider.

References

Burke, Kenneth. (1966). Language as Symbolic Action. Lost Angeles: University of California Press.

Phillips, Whitney. (2015). Let's call 'trolling' what it really is. The Kernel. Retrieved from https://kernelmag.dailydot.com/issue-sections/staff-editorials/12898/trolling-stem-tech-sexism/

Sparby, Erika M. (2017). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric on 4chan. Computers and Composition, 45, pp. 85-97.

Phillips, Whitney. (2015). Let's call 'trolling' what it really is. The Kernel. Retrieved from https://kernelmag.dailydot.com/issue-sections/staff-editorials/12898/trolling-stem-tech-sexism/

Sparby, Erika M. (2017). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric on 4chan. Computers and Composition, 45, pp. 85-97.