© Erika M. Sparby

Ethical meming—How can we meme inclusively?

Keynote presented at 2019 LangRhet conference

Content warning: mentions of rape, stalking, and suicide

|

In early 2019, I participated in a Facebook Live Q&A with Know Your Meme Janitor-in-Chief Brad Kim. I asked him if he thought memes should have an ethical component. With over a decade of meme expertise under his belt, I was curious to know what the real memelords thought about my idea that memetic production, reproduction, and propagation could and should follow ethical guidelines. Unfortunately, given the nature of the Q&A format, I was unable to clarify my question or ask follow up questions (although I tried to, I’m not sure Brad saw them). And very shortly into his answer it became clear that Brad and I were operating from a very different idea of what “ethics” and an “ethic of meming” might mean.

|

Brad thought of it as more of a code of rules, stating that “Ethics of meming is hard to, I think… [long pause]. It’s probably easier to define, but harder to build a consensus on, or even to govern, or enforce" (Know Your Meme, 2019). Further, he argued that the very nature of a meme is amoral, but also “ethically malleable,” meaning, I think, that memes can be adapted to serve a wide variety of purposes. He ends by stating, “I can’t quite picture that" (Know Your Meme, 2019).

However, digital rhetorics as a field tends to conceptualize ethics as less of a governing principle and more of a guiding force. Jim Porter (1998) first defined “rhetorical ethics” as a “set of implicit understandings between writer and audience about their relationship" (p. 68), and Jim Brown (2015) built on this to show that networks of human and nonhuman agents have rhetorical implications in digital spaces. Through taking an ethical approach to technology, we can easily see, as Cindy Selfe and Richard Selfe (1991) have pointed out, that digital networks and the works that circulate within and through them are not neutral, including memes, meme producers and sharers, and memetic spaces. And as I argued elsewhere, once we are aware of a need for an ethical intervention in memetic behaviors, it is our responsibility as rhetoricians to make “users aware of their culpability if and when they acquiesce to and participate in these [damaging] memetic behaviors" (Sparby, 2014, p. 94).

So then the question is, what is unethical memetic creation? I’m currently working on a book project tentatively titled Rhetorical Memetic Ethics: Rhetoric, Identity, and What It Means to Meme Ethically that seeks to answer this question, among others. I plan to explore ethical meming in regards to many identity factors, such as gender, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, economic status, and ability. Specifically, I am looking at how and why memes are often used to both intentionally and unintentionally reinforce marginalizing power structures in popular, mainstream, and counter cultural spaces while also arguing for ways to meme inclusively. My talk tonight comes from chapter three, tentatively titled “Adding an Ethical Element to the Memetic Rhetorical Toolkit—Privacy and Ethics of Use,” which examines an overarching ethical concern relevant to all aspects of identity and inclusion: privacy.

Before I dig in, it’s helpful to define what I mean when I say “meme,” since it differs a bit from popular parlance. Whenever I tell people I’m writing a book about memes, I get some variation of the same response, “Oh my gosh I love memes! Have you seen [insert meme here]? It’s one of my favorites!” And unless that person and I have similar interests and/or circulate through the same digital communities, my answer is usually “no, I haven’t—show it to me!” Then our conversation usually proceeds somewhere along the lines of, “If you’re researching memes, how do you not know this one?” There are millions of memes (billions? more? is it even possible/feasible to try to count?). It’s impossible for even the most hardcore memer—which I am not—to stay on top of them all.

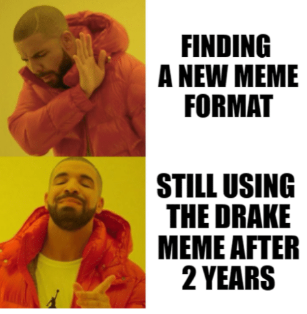

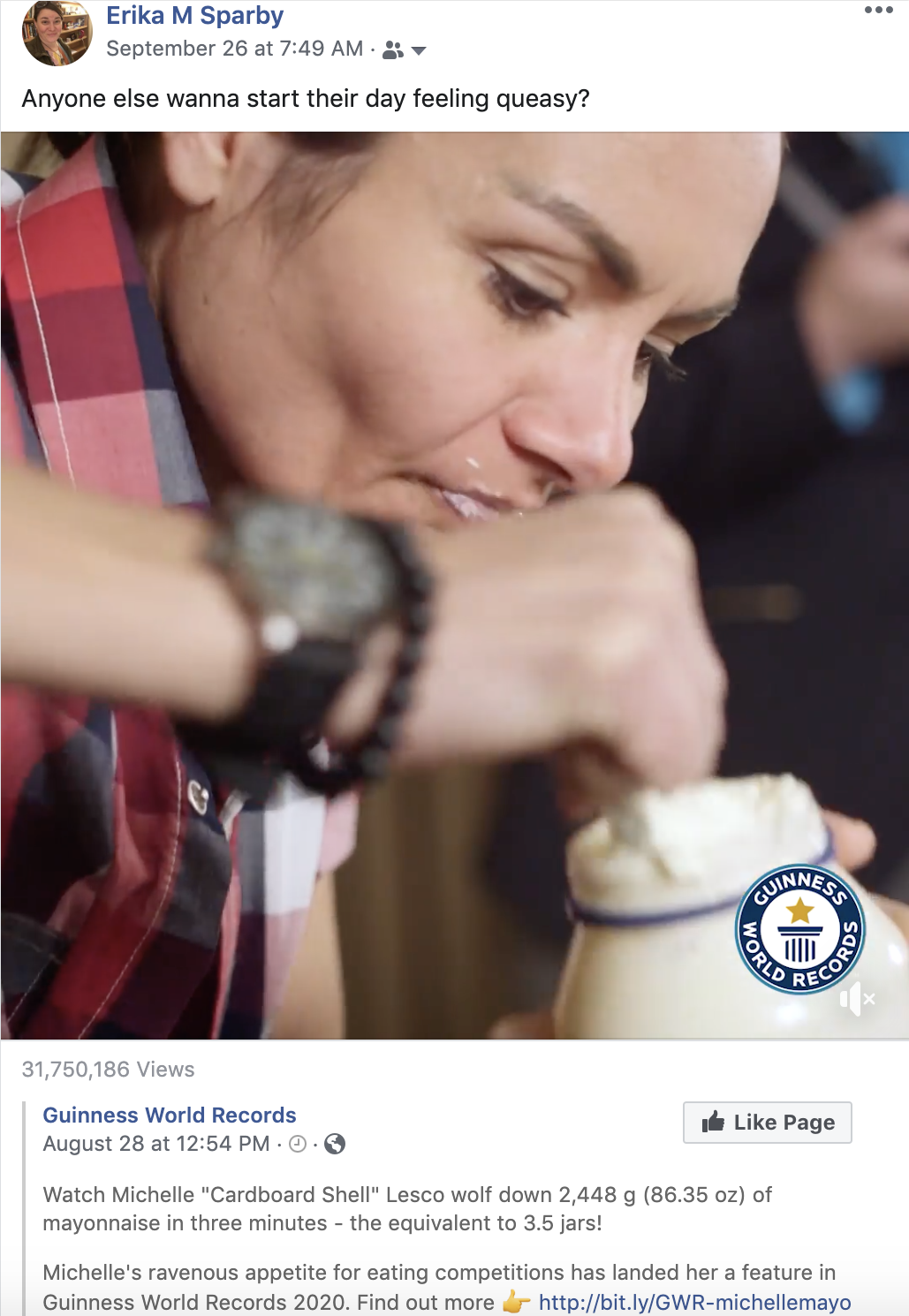

I’ve also had friends ask me, “what, exactly, are memes? Like, what makes them different from really popular or viral content?” I explain that the core difference between the two is adaptability. If something is recirculated without any changes to its rhetorical existence, it’s viral; but if the sharer changes, removes, or adds a rhetorical element, it’s memetic. But even this definition is admittedly confusing. If I change the text on this image, is it a meme? Yes. But if I reshare this YouTube video on Facebook, is it a meme? Well, that depends. Did I say something about the video when I posted it? If so, this new textual framework is a new rhetorical element that remixes and recontextualizes the original text. I argue that even if the Facebook post itself is not a meme, the very act of posting links of YouTube videos to our Facebook timelines is a memetic behavior that we have developed in tandem with digital technologies as they have enabled us to do so. This is an important distinction to make. Memes are texts that can be shared and recirculated, but memetic behaviors are the forces that drive sharing and recirculation. This also leads to an important question: are all of our digital behaviors (or even our analog behaviors) memetic? To some extent, yes. We are driven by social, cultural, and technological affordances to behave according to certain social, cultural, and technological expectations. I find this realization empowering because once we see and understand the memetic patterns we tend to fall into in digital spaces, we can take control of and change them if we need to.

However, digital rhetorics as a field tends to conceptualize ethics as less of a governing principle and more of a guiding force. Jim Porter (1998) first defined “rhetorical ethics” as a “set of implicit understandings between writer and audience about their relationship" (p. 68), and Jim Brown (2015) built on this to show that networks of human and nonhuman agents have rhetorical implications in digital spaces. Through taking an ethical approach to technology, we can easily see, as Cindy Selfe and Richard Selfe (1991) have pointed out, that digital networks and the works that circulate within and through them are not neutral, including memes, meme producers and sharers, and memetic spaces. And as I argued elsewhere, once we are aware of a need for an ethical intervention in memetic behaviors, it is our responsibility as rhetoricians to make “users aware of their culpability if and when they acquiesce to and participate in these [damaging] memetic behaviors" (Sparby, 2014, p. 94).

So then the question is, what is unethical memetic creation? I’m currently working on a book project tentatively titled Rhetorical Memetic Ethics: Rhetoric, Identity, and What It Means to Meme Ethically that seeks to answer this question, among others. I plan to explore ethical meming in regards to many identity factors, such as gender, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, economic status, and ability. Specifically, I am looking at how and why memes are often used to both intentionally and unintentionally reinforce marginalizing power structures in popular, mainstream, and counter cultural spaces while also arguing for ways to meme inclusively. My talk tonight comes from chapter three, tentatively titled “Adding an Ethical Element to the Memetic Rhetorical Toolkit—Privacy and Ethics of Use,” which examines an overarching ethical concern relevant to all aspects of identity and inclusion: privacy.

Before I dig in, it’s helpful to define what I mean when I say “meme,” since it differs a bit from popular parlance. Whenever I tell people I’m writing a book about memes, I get some variation of the same response, “Oh my gosh I love memes! Have you seen [insert meme here]? It’s one of my favorites!” And unless that person and I have similar interests and/or circulate through the same digital communities, my answer is usually “no, I haven’t—show it to me!” Then our conversation usually proceeds somewhere along the lines of, “If you’re researching memes, how do you not know this one?” There are millions of memes (billions? more? is it even possible/feasible to try to count?). It’s impossible for even the most hardcore memer—which I am not—to stay on top of them all.

I’ve also had friends ask me, “what, exactly, are memes? Like, what makes them different from really popular or viral content?” I explain that the core difference between the two is adaptability. If something is recirculated without any changes to its rhetorical existence, it’s viral; but if the sharer changes, removes, or adds a rhetorical element, it’s memetic. But even this definition is admittedly confusing. If I change the text on this image, is it a meme? Yes. But if I reshare this YouTube video on Facebook, is it a meme? Well, that depends. Did I say something about the video when I posted it? If so, this new textual framework is a new rhetorical element that remixes and recontextualizes the original text. I argue that even if the Facebook post itself is not a meme, the very act of posting links of YouTube videos to our Facebook timelines is a memetic behavior that we have developed in tandem with digital technologies as they have enabled us to do so. This is an important distinction to make. Memes are texts that can be shared and recirculated, but memetic behaviors are the forces that drive sharing and recirculation. This also leads to an important question: are all of our digital behaviors (or even our analog behaviors) memetic? To some extent, yes. We are driven by social, cultural, and technological affordances to behave according to certain social, cultural, and technological expectations. I find this realization empowering because once we see and understand the memetic patterns we tend to fall into in digital spaces, we can take control of and change them if we need to.

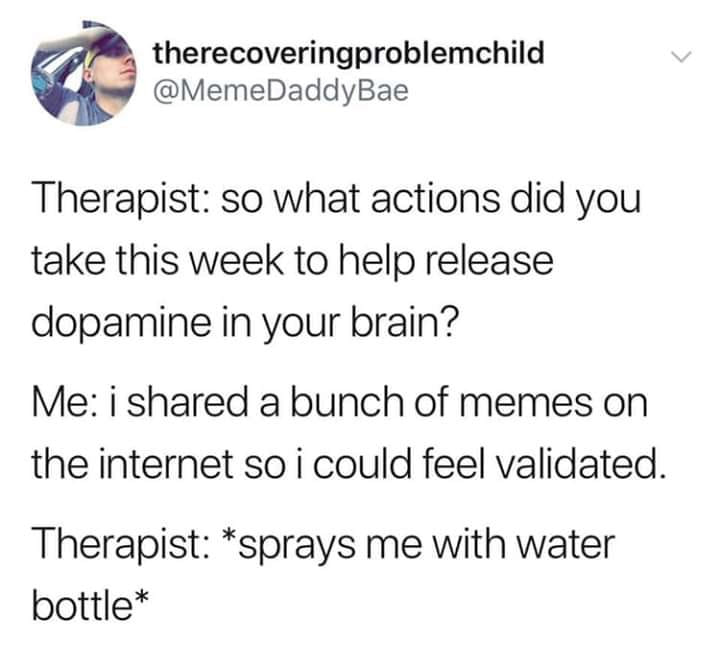

Now that I’ve established a working definition of memes and memetic behaviors, I’ll move into talking about memes and privacy. Memes, especially image-based ones but also reshared tweets and posts with names and other identity markers attached, often appropriate anonymous figures to represent the identity of an implied person or group of people. See for instance these example memes of the Side Eye Girl and a screencap of an Instagram post in what I call the Theraposting format. The first is a reaction image used to respond to digital exchanges, usually in lieu of text. The second is an ironic style of meme that hinges on self-deprecating humor to call attention to both the importance of mental health and self-destructive behaviors that undermine therapy. Notice that the user’s name and picture have been circulated with the screencap, attaching his identity to it.

This practice of using these kinds of images and screencaps for memes is similar to what Cagle (2019) calls “strangershots.” In this genre of photograph, the subject is unaware that a photo is being taken of them; the photo is then posted online, usually for the purpose of ridicule, which is understood by many to be an unethical violation of privacy. I operate from Cagle’s definition of privacy as “a more general way to highlight people’s varied expectations of surveillance on the street, in businesses, on college campuses, and across other spaces that range from clearly public to quasi-public to self-evidently private" (p. 69). I supplement it with former Federal Trade Commissioner Julie Brill’s redefinition of privacy for the digital age: "individuals cherish being connected, shopping online and through apps, and sharing with friends and colleagues through social networks, but believe that their online activities shouldn’t be subject to invasive monitoring… I think the meaning of privacy now also includes an individual’s right to have some control over their online persona and destiny" (qtd. in Selinger and Woodrow, 2015). Privacy, then, is twofold: 1) an expected ability to move through spaces and perform activities without being surveilled; 2) a desired ability to control how identity is presented in digital spaces. The differentiation between expectation and desire here is intentional. We expect that we can move throughout digital spaces without surveillance; even though doing so is very difficult, we think it should be the default setting on digital practices. At the same time, we desire to take control of our digital identity. Even though many do not know how to, we wish we could.

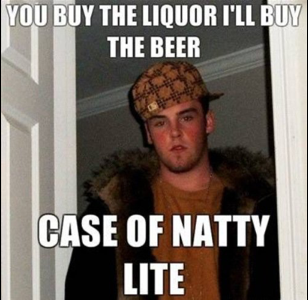

Memes complicate our expectations and desires for privacy. Image memes function similarly to the strangershots Cagle describes in their ability to disrupt privacy. Some of the most popular ones from early meme culture include Scumbag Steve, whose real name is Blake Boston and whose photo was taken from his mom’s Flickr account; he becomes a stand-in for inconsiderate friends. Another one is Overly Attached Girlfriend, whose real name is Laina Morris and who became a meme after someone took a screencap of a parody video; she becomes a representation of a clingy significant other. Each of these image memes and ones like them use images of the central figures without their knowledge or consent. Jasmine Garsd (2015) explains, “All these Internet celebrities have one thing in common: They didn’t intend to become famous. Their pictures just happened to go viral.”

Memes complicate our expectations and desires for privacy. Image memes function similarly to the strangershots Cagle describes in their ability to disrupt privacy. Some of the most popular ones from early meme culture include Scumbag Steve, whose real name is Blake Boston and whose photo was taken from his mom’s Flickr account; he becomes a stand-in for inconsiderate friends. Another one is Overly Attached Girlfriend, whose real name is Laina Morris and who became a meme after someone took a screencap of a parody video; she becomes a representation of a clingy significant other. Each of these image memes and ones like them use images of the central figures without their knowledge or consent. Jasmine Garsd (2015) explains, “All these Internet celebrities have one thing in common: They didn’t intend to become famous. Their pictures just happened to go viral.”

Similarly, a common trend in memes is to screencap tweets or other social media posts to share across platforms. While the tweet itself may not be a meme, the behavior of screencapping and sharing is. However, often these posts also include users’ names, such as the tweet I showed a moment ago, which can lead to them being outed in a variety of digital spaces for the content they post. True, many of these kinds of posts—especially tweets—are often public, but even so users tend to have a general idea of who their followers are and what they can expect their reach to be; most likely do not anticipate their posts leaving the original platform and appearing in another.

The unwitting fame that results from having a photo or name circulate as part of a meme can have a huge impact on the figure’s or user’s life. For some, it leads to further fame, but for others it can lead to intense psychological issues and/or real-life harassment. In the next part of this talk, I will present a number of case studies that consider unethical memetic creation and circulation relating to privacy, building toward a heuristic for ethical meming that includes privacy.

The unwitting fame that results from having a photo or name circulate as part of a meme can have a huge impact on the figure’s or user’s life. For some, it leads to further fame, but for others it can lead to intense psychological issues and/or real-life harassment. In the next part of this talk, I will present a number of case studies that consider unethical memetic creation and circulation relating to privacy, building toward a heuristic for ethical meming that includes privacy.

Exploiting Identity to Capitalize on Memetic Fame

In 2010, Antoine Dodson was interviewed by an NBC news affiliate in Alabama the morning after his sister woke up in the middle of the night to a strange man trying to climb into bed with her. A flustered Dodson looked at the camera and made some exaggerated statements and claims, including his most famous line: “hide yo’ kids, hide yo’ wife, hide yo’ husbands, ‘cuz they rapin’ everybody up in here.” His interview was remixed into an autotuned song called “Bed Intruder” that was available for purchase on iTunes and a music video that appeared on YouTube. “Antoine Dodson / Bed Intruder” was one of the first viral autotuned news footage videos, with “Eccentric Witness Lady” following later in 2010 (Know Your Meme, 2011), “Sweet Brown” in 2012 (Know Your Meme, 2012b), and “It’s Poppin” in 2016 (Know Your Meme, 2016). Even Daym Drops, a food vlogger, found one of his reviews had been autotuned and was seeing viral success in 2012 (Know Your Meme, 2013). A quick note about these screencaps: none of these are flattering images of these meme figures, but they are the images that were circulated most frequently with their videos and songs. I show them here so you can understand that the visual representation that often gets attached to these people’s names and reputations can be damaging.

There is one thing all of these meme figures had in common: they did not consent to be featured in the initial release of their autotuned remixes. Although he likely expected that his interview would be aired on television and available on the news website, Dodson was surprised by his rise to memetic fame with the popularity of the “Bed Intruder” video, but he embraced it and used his public recognition to initiate his own career. He created a website, started a YouTube channel, and tried to pilot a reality TV show centered on him and his siblings (Know Your Meme, 2010). He performed his song live at the BET Awards. Dodson has seen moderate financial success through these endeavors(Scott, 2018). On the other hand, the Gregory Brothers, the YouTubers who created most of the autotuned videos and others have seen quite a bit more. This quartet of YouTubers rose to fame with Dodson’s video and is best known for their Songify the News series. Although they produce some original content, they have largely made their career out of songifying videos featuring other people. While the Gregory Brothers have Songified over 90 instances of public speaking ranging from an old Winston Churchill speech to a mashup of scenes from Rick and Morty, “Bed Intruder” remains one of their most popular videos with nearly 150 billion views. In the case of Dodson, the group signed a deal with him so that he would receive 50% of the profits from the iTunes sales, but it’s unclear if others have received the same treatment. In addition, their channel and videos are monetized, which essentially means they receive money for views and they have won awards for their Songified productions.

These videos also largely feature people of color, lower income people, and/or people with cognitive disabilities. As you can see here, the Gregory Brothers are all white, probably middle class, and able-bodied—as are many of their fans—so it appears that the laughter they invoke at these videos serves as a shaming mechanism, whether they intend it to be so or not. As Cagle (2019) describes, “shaming serves a policing function; it tells us what’s acceptable and what isn’t, which bodies are supposed to appear in public and which aren’t, which behaviors are socially permissible and which aren’t" (p. 74). And so, people laugh at the exploitation of perceived abnormality of expression when describing a distressing or exciting event. As Charles Williams (2013) explains in his reflection on why laugher at these videos could be seen as racist, what we see in these videos is people who refuse to code switch for the camera and are then seen as ignorant, other, or weird: “What the two are doing when they speak so bluntly and passionately, with a hybrid Southern and urban twang, is using the language their communities have given them.” But then a memer comes along, sees the videos and their potential for humor, remixes it, and exploits their identities and perceived otherness for capital gain.

There is one thing all of these meme figures had in common: they did not consent to be featured in the initial release of their autotuned remixes. Although he likely expected that his interview would be aired on television and available on the news website, Dodson was surprised by his rise to memetic fame with the popularity of the “Bed Intruder” video, but he embraced it and used his public recognition to initiate his own career. He created a website, started a YouTube channel, and tried to pilot a reality TV show centered on him and his siblings (Know Your Meme, 2010). He performed his song live at the BET Awards. Dodson has seen moderate financial success through these endeavors(Scott, 2018). On the other hand, the Gregory Brothers, the YouTubers who created most of the autotuned videos and others have seen quite a bit more. This quartet of YouTubers rose to fame with Dodson’s video and is best known for their Songify the News series. Although they produce some original content, they have largely made their career out of songifying videos featuring other people. While the Gregory Brothers have Songified over 90 instances of public speaking ranging from an old Winston Churchill speech to a mashup of scenes from Rick and Morty, “Bed Intruder” remains one of their most popular videos with nearly 150 billion views. In the case of Dodson, the group signed a deal with him so that he would receive 50% of the profits from the iTunes sales, but it’s unclear if others have received the same treatment. In addition, their channel and videos are monetized, which essentially means they receive money for views and they have won awards for their Songified productions.

These videos also largely feature people of color, lower income people, and/or people with cognitive disabilities. As you can see here, the Gregory Brothers are all white, probably middle class, and able-bodied—as are many of their fans—so it appears that the laughter they invoke at these videos serves as a shaming mechanism, whether they intend it to be so or not. As Cagle (2019) describes, “shaming serves a policing function; it tells us what’s acceptable and what isn’t, which bodies are supposed to appear in public and which aren’t, which behaviors are socially permissible and which aren’t" (p. 74). And so, people laugh at the exploitation of perceived abnormality of expression when describing a distressing or exciting event. As Charles Williams (2013) explains in his reflection on why laugher at these videos could be seen as racist, what we see in these videos is people who refuse to code switch for the camera and are then seen as ignorant, other, or weird: “What the two are doing when they speak so bluntly and passionately, with a hybrid Southern and urban twang, is using the language their communities have given them.” But then a memer comes along, sees the videos and their potential for humor, remixes it, and exploits their identities and perceived otherness for capital gain.

Compromised Safety as A Result of Memetic Fame

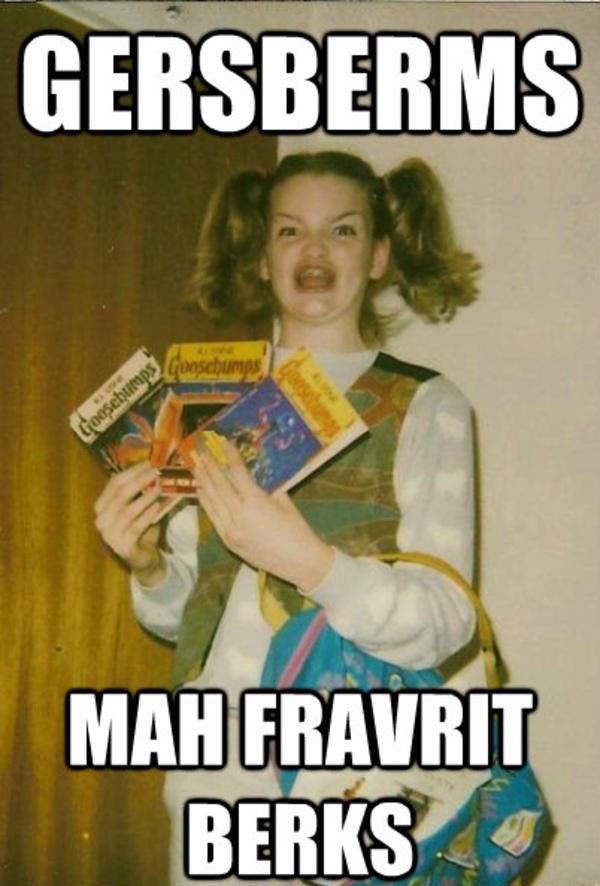

While browsing through a friend’s Facebook page, a Reddit user found a photo of an awkward adolescent girl who is incredibly excited about the Goosebumps books she is holding. He didn’t know the girl in the photo, nor does he remember whose photos he was browsing, but he uploaded it to r/funny on Reddit (King, 2015). In an interview, he stated that he “didn’t think much of it at the time” (King, 2015). Later, another Redditor stumbled across the image and added text that you see here: “GERSBERMS / MAH FAVRIT BERKS,” a slurred version of “Goosebumps / My favorite books.” Later iterations of the meme generally include “Ermahgerd,” or “oh my god,” in the top line, which is where the meme gets its name. The strange spelling is meant to indicate a verbal distortion akin to “retainer lisp,” or an exaggeration of how it sounds when someone speaks while wearing a retainer (Know Your Meme, 2012a). Other versions of the meme show “Berks” (Ermahgerd-speak for “books,” the name given to the meme’s central figure) holding other various objects with equal excitement and speaking with her signature mispronunciation.

Although the Ermagerd meme seems innocuous, it also highlights one of the dangers behind a meme figure being identified. In March 2012, Reddit used their sleuthing skills to discover that the central figure behind the meme was Maggie Goldenberger. First, a user posted a picture of Goldenberger with the text “ERMAHGERD / I’M HOT.” The next day, another user posted a side-by-side facial comparison of the meme with Goldenberger, concluding that it was “plausible” the two were of the same woman. It’s not clear where the user found this photo or how they began to draw connections between it and the meme. As users attempted to find the real “Berks,” Goldenberger was outed as the woman behind the meme. At one point, someone hired a bounty hunter to find and take pictures of her and a photo of her on vacation in Hawaii on a beach wearing a bikini surfaced online (King, 2015), which proved a potentially dangerous invasion of her privacy. Goldenberger managed to keep a sense of humor about the whole ordeal, which she deemed “the only really hurtful episode of the experience.” She joked, “if I’m going to have a bikini shot floating around on the Internet, I’d like to be spray tanned and under a waterfall somewhere” (as quoted in King, 2015). Although she laughs off the experience after the fact, she admits it was unsettling and even scary to watch her real-life identity be revealed and attached to her photo and then to realize that someone was watching her unwittingly.

It’s important to note that in Goldenberger’s situation, her privacy violation was uniquely gendered. Had she been a man, she likely would still be identified, but not with the text “ermahgerd I’m hot” added to her image. Similarly, it’s hard to imagine someone hiring a bounty hunter to take bathing suit pictures of male meme figures. In fact, while meme figures such as Scumbag Steve and Ridiculously Photogenic Guy have been identified as Blake Boston and Zeddie Little, neither have received the same stalker-ish treatment that Goldenberger has. This is particularly interesting because the very purpose of Little’s meme was to objectify him for being good looking. The image comes from a photo snapped of him mid-marathon where he just happened to look up and smile at the right time while everyone else around him looks miserable. Much of the text across various iterations makes jokes about his attractiveness. On the flipside, Goldenberger’s meme depicts her at a young age intentionally making a silly face and wearing mismatched clothes. As such, it seems reasonable to say that Goldenberger was stalked because she is a memetic figure and a woman, and not only the former.

Although the Ermagerd meme seems innocuous, it also highlights one of the dangers behind a meme figure being identified. In March 2012, Reddit used their sleuthing skills to discover that the central figure behind the meme was Maggie Goldenberger. First, a user posted a picture of Goldenberger with the text “ERMAHGERD / I’M HOT.” The next day, another user posted a side-by-side facial comparison of the meme with Goldenberger, concluding that it was “plausible” the two were of the same woman. It’s not clear where the user found this photo or how they began to draw connections between it and the meme. As users attempted to find the real “Berks,” Goldenberger was outed as the woman behind the meme. At one point, someone hired a bounty hunter to find and take pictures of her and a photo of her on vacation in Hawaii on a beach wearing a bikini surfaced online (King, 2015), which proved a potentially dangerous invasion of her privacy. Goldenberger managed to keep a sense of humor about the whole ordeal, which she deemed “the only really hurtful episode of the experience.” She joked, “if I’m going to have a bikini shot floating around on the Internet, I’d like to be spray tanned and under a waterfall somewhere” (as quoted in King, 2015). Although she laughs off the experience after the fact, she admits it was unsettling and even scary to watch her real-life identity be revealed and attached to her photo and then to realize that someone was watching her unwittingly.

It’s important to note that in Goldenberger’s situation, her privacy violation was uniquely gendered. Had she been a man, she likely would still be identified, but not with the text “ermahgerd I’m hot” added to her image. Similarly, it’s hard to imagine someone hiring a bounty hunter to take bathing suit pictures of male meme figures. In fact, while meme figures such as Scumbag Steve and Ridiculously Photogenic Guy have been identified as Blake Boston and Zeddie Little, neither have received the same stalker-ish treatment that Goldenberger has. This is particularly interesting because the very purpose of Little’s meme was to objectify him for being good looking. The image comes from a photo snapped of him mid-marathon where he just happened to look up and smile at the right time while everyone else around him looks miserable. Much of the text across various iterations makes jokes about his attractiveness. On the flipside, Goldenberger’s meme depicts her at a young age intentionally making a silly face and wearing mismatched clothes. As such, it seems reasonable to say that Goldenberger was stalked because she is a memetic figure and a woman, and not only the former.

Psychological Trauma as a result of Memetic Fame

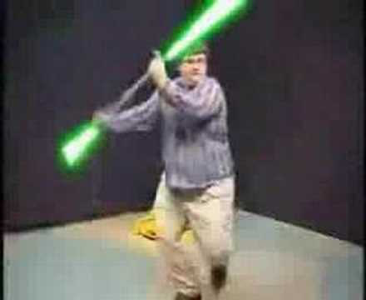

In 2002, 14-year-old Ghyslain Raza used his high school’s AV room and equipment to record himself pretending to be a Jedi fighting off enemies with a double-sided light saber. He forgot to take the tape out before he left, and some other students found Raza’s recording a few months later and posted it online (Know Your Meme, 2008). The short video spread far and fast. Memers remixed the footage several times, but the most notable ones replaced Raza’s pole with a double-edged lightsaber and added laser bullets for him to deflect, à la Star Wars. Thus, Star Wars Kid, one of the first widespread Internet memes, was born. Viewers found the video humorous; some related to Raza’s awkward fantasy recreation, others laughed cruelly at an overweight kid staging a fantasy battle, another shaming mechanism similar to laughing at Dodson and other Songified figures.

However, Raza did not see any humor in the experience. Instead, “he and his parents regarded [the video’s being shared online] as being cruel and invasive" (Knobel & Lankshear, 2007, p. 223). He was also “bullied incessantly, to the point that he became depressed and dropped out of school to go to a children’s psychiatric ward” Garsd (2015). His parents also sued the classmates who posted the video. Not only was he bullied at school, but he was also cyberbullied online. Raza explains that when he read comments about the meme online, “What I saw was mean. It was violent. People were telling me to commit suicide” (“10 Years Later,” 2013). He elaborates: “it was a very dark period…. No matter how hard I tried to ignore people telling me to commit suicide, I couldn’t help but feel worthless, like my life wasn’t worth living” (“10 Years Later,” 2013).

Star Wars Kid also earned Raza some fans who saw the vitriolic response to the meme and wanted to show him their support. Together they raised over $4000 to buy him an iPod and put the rest on a gift card (Baio, 2003), but he did not respond to the gift. Others even signed a petition to give him a cameo role in the upcoming Star Wars III movie, but nothing came of it. Even with the positive support from his fans, the whole Star Wars Kid experience was and continues to be traumatic for Raza. As of a 2013 interview, one of very few public appearances he’s made since Star Wars Kid appeared, he is a law school graduate and anti-cyberbullying advocate.

However, Raza did not see any humor in the experience. Instead, “he and his parents regarded [the video’s being shared online] as being cruel and invasive" (Knobel & Lankshear, 2007, p. 223). He was also “bullied incessantly, to the point that he became depressed and dropped out of school to go to a children’s psychiatric ward” Garsd (2015). His parents also sued the classmates who posted the video. Not only was he bullied at school, but he was also cyberbullied online. Raza explains that when he read comments about the meme online, “What I saw was mean. It was violent. People were telling me to commit suicide” (“10 Years Later,” 2013). He elaborates: “it was a very dark period…. No matter how hard I tried to ignore people telling me to commit suicide, I couldn’t help but feel worthless, like my life wasn’t worth living” (“10 Years Later,” 2013).

Star Wars Kid also earned Raza some fans who saw the vitriolic response to the meme and wanted to show him their support. Together they raised over $4000 to buy him an iPod and put the rest on a gift card (Baio, 2003), but he did not respond to the gift. Others even signed a petition to give him a cameo role in the upcoming Star Wars III movie, but nothing came of it. Even with the positive support from his fans, the whole Star Wars Kid experience was and continues to be traumatic for Raza. As of a 2013 interview, one of very few public appearances he’s made since Star Wars Kid appeared, he is a law school graduate and anti-cyberbullying advocate.

Losing Employment Over A Tweet

|

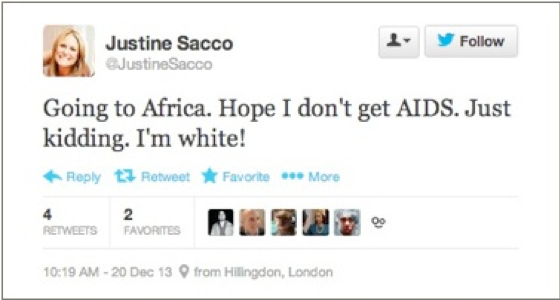

In 2013, Justine Sacco posted a series of tweets to her 170 followers about air travel while on her way to Africa. Most of her tweets were pretty innocuous, but one gained her notoriety and cost her her job. During the 11-hour flight, she became a viral sensation on and beyond Twitter. Ronson (2015), a journalist for the New York Times, explains, “The furor over Sacco’s tweet had become not just an ideological crusade against her perceived bigotry but also a form of idle entertainment. Her complete ignorance of her predicament for those 11 hours lent the episode both dramatic irony and a pleasing narrative arc.”

|

By the time she had landed, the hashtag #hasjustinelandedyet was trending on Twitter, with people’s reactions spanning anywhere from amusement at her predicament to confusion over how she had a job as a senior director of corporate communications to anger and criticism for her casual racism. Sacco’s tweet had received hundreds of thousands of comments and shares; it was screencapped and recirculated in a variety of media, even after she had her friend delete the tweet and her account shortly after landing. Before the plane had even touched down, Sacco was fired.

While I agree that her tweet, while perhaps misguided, is nonetheless quite racist and I have no intention to dispute that sentiment, her high-profile case provides an important example of what happens when a tweet or other social media post recirculates beyond not only the intended audience, but any possible conception of who the audience could be. Ronson (2015) interviewed her a few weeks after the event to get her take on everything. In her interview and a follow up email, she claimed that she was not trying to be racist, and that she doesn’t actually believe white people don’t get AIDS. Instead, she was trying to critique her own privilege she has as a white American: “To put it simply, I wasn’t trying to raise awareness of AIDS or piss off the world or ruin my life. Living in America puts us in a bit of a bubble when it comes to what is going on in the third world. I was making fun of that bubble" (Ronson, 2015). Clearly, Sacco’s intended message does not come through in her tweet.

But what strikes me about this case is how public it is from beginning to end, and it’s this very public nature that raises some important questions. Had Sacco said something similar to one of her colleagues while in the board room, would she still have been fired? Depending on the colleague, probably not. If her tweet had not gone viral and received international attention, would she have lost her job? Almost certainly not, since during her flight some users took a deep dive into her account and found some other offensive tweets that had yet to lose her a job. And then there’s the even harder to answer question: did she deserve to lose her job over this tweet? Or, should her company have publicly fired her over a tweet that was unrelated to her job? The answer to these questions is even trickier, and I’m not convinced there is one.

But the question that keeps me up at night is this one: was it ethical to publicly shame Sacco because of her tweets? On the one hand, I want to say yes. On the other hand, if we say it’s okay to publicly shame Sacco, then is it also okay to publicly shame people in the strangershots Cagle (2019) studies or the Songified memes I talked about earlier? Like with doxing, it seems to me that if we say one is ethically permissible, then we have to say that the other one is too. Doxing, short for “dropping docs,” is the act of making a person’s personal information—address, phone number, social security number, credit cards, and so on—public as a way to threaten them. I bring it up because there is a debate about whether or not there can be such a thing as “good doxing” or ethical doxing. When the Charlottesville rioters’ photos were circulated after the event, users took to Twitter to identify them and then outed them to family, friends, and employers. Many lost their jobs and suffered other consequences (Ellis, 2017; Miller, 2018). Doxers felt justified in their actions by calling out white supremacy and white nationalism and forcing its proponents to face some kind of negative effect as a result of their racist beliefs.

However, as someone who studies online aggression and has fresh memories of watching in horror as Anita Sarkeesian and Zoe Quinn were doxed as part of GamerGate for calling out toxic masculinity—which many, including myself, would consider “bad doxing”—I am forced to admit that even when people are engaging in what we might call unethical doxing, they think they are being ethical. Regardless of how misguided and amoral GamerGate may have been from my perspective, many proponents felt justified in their actions in much the same way the Charlottesville doxers did. I’m not necessarily a relativist, but I want to be careful about what we say is ethical and unethical. If we say the Charlottesville doxing is okay but not the GamerGate doxing, then we are only creating a further divide between two sides by telling them “it’s okay when we do this thing that has serious consequences on you, but not for you to do it to us.” This approach doesn’t tend to have a lot of rhetorical success in changing minds and may in fact make them hold their beliefs even tighter, as Jared Colton has pointed out (in Ellis, 2017).

And so, I return to the question from a few moments ago: is it ethical to publicly shame people the way Sacco was shamed over her tweet? It’s hard to say, but in this case it seems there was no other option because of the thorough publicity of the event. On the one hand she knew her tweet was public and that it could spread beyond her immediate network, even if she did not expect it to. On the other hand, how could she ever have conceived that it would spread as far and wide as it did in such a short amount of time? I’m of the mind that, because of the overwhelming publicity of the event, there is no way that her employer could have handled it privately without themselves facing repercussions, but it seems like it should have been a matter left between them and Sacco. But because of the reach and response of social media, any semblance of privacy in this case was impossible, which also means any remorse Sacco may show for the tweet is suspect since she may be operating according to public expectations instead of her private beliefs.

While I agree that her tweet, while perhaps misguided, is nonetheless quite racist and I have no intention to dispute that sentiment, her high-profile case provides an important example of what happens when a tweet or other social media post recirculates beyond not only the intended audience, but any possible conception of who the audience could be. Ronson (2015) interviewed her a few weeks after the event to get her take on everything. In her interview and a follow up email, she claimed that she was not trying to be racist, and that she doesn’t actually believe white people don’t get AIDS. Instead, she was trying to critique her own privilege she has as a white American: “To put it simply, I wasn’t trying to raise awareness of AIDS or piss off the world or ruin my life. Living in America puts us in a bit of a bubble when it comes to what is going on in the third world. I was making fun of that bubble" (Ronson, 2015). Clearly, Sacco’s intended message does not come through in her tweet.

But what strikes me about this case is how public it is from beginning to end, and it’s this very public nature that raises some important questions. Had Sacco said something similar to one of her colleagues while in the board room, would she still have been fired? Depending on the colleague, probably not. If her tweet had not gone viral and received international attention, would she have lost her job? Almost certainly not, since during her flight some users took a deep dive into her account and found some other offensive tweets that had yet to lose her a job. And then there’s the even harder to answer question: did she deserve to lose her job over this tweet? Or, should her company have publicly fired her over a tweet that was unrelated to her job? The answer to these questions is even trickier, and I’m not convinced there is one.

But the question that keeps me up at night is this one: was it ethical to publicly shame Sacco because of her tweets? On the one hand, I want to say yes. On the other hand, if we say it’s okay to publicly shame Sacco, then is it also okay to publicly shame people in the strangershots Cagle (2019) studies or the Songified memes I talked about earlier? Like with doxing, it seems to me that if we say one is ethically permissible, then we have to say that the other one is too. Doxing, short for “dropping docs,” is the act of making a person’s personal information—address, phone number, social security number, credit cards, and so on—public as a way to threaten them. I bring it up because there is a debate about whether or not there can be such a thing as “good doxing” or ethical doxing. When the Charlottesville rioters’ photos were circulated after the event, users took to Twitter to identify them and then outed them to family, friends, and employers. Many lost their jobs and suffered other consequences (Ellis, 2017; Miller, 2018). Doxers felt justified in their actions by calling out white supremacy and white nationalism and forcing its proponents to face some kind of negative effect as a result of their racist beliefs.

However, as someone who studies online aggression and has fresh memories of watching in horror as Anita Sarkeesian and Zoe Quinn were doxed as part of GamerGate for calling out toxic masculinity—which many, including myself, would consider “bad doxing”—I am forced to admit that even when people are engaging in what we might call unethical doxing, they think they are being ethical. Regardless of how misguided and amoral GamerGate may have been from my perspective, many proponents felt justified in their actions in much the same way the Charlottesville doxers did. I’m not necessarily a relativist, but I want to be careful about what we say is ethical and unethical. If we say the Charlottesville doxing is okay but not the GamerGate doxing, then we are only creating a further divide between two sides by telling them “it’s okay when we do this thing that has serious consequences on you, but not for you to do it to us.” This approach doesn’t tend to have a lot of rhetorical success in changing minds and may in fact make them hold their beliefs even tighter, as Jared Colton has pointed out (in Ellis, 2017).

And so, I return to the question from a few moments ago: is it ethical to publicly shame people the way Sacco was shamed over her tweet? It’s hard to say, but in this case it seems there was no other option because of the thorough publicity of the event. On the one hand she knew her tweet was public and that it could spread beyond her immediate network, even if she did not expect it to. On the other hand, how could she ever have conceived that it would spread as far and wide as it did in such a short amount of time? I’m of the mind that, because of the overwhelming publicity of the event, there is no way that her employer could have handled it privately without themselves facing repercussions, but it seems like it should have been a matter left between them and Sacco. But because of the reach and response of social media, any semblance of privacy in this case was impossible, which also means any remorse Sacco may show for the tweet is suspect since she may be operating according to public expectations instead of her private beliefs.

Public Failure and the “Right to Be Forgotten

I chose these four examples intentionally because they highlight how identity is tied to ethical meming and privacy. Antoine Dodson’s experience highlights how memes can parody tropes of African American Vernacular English; Maggie Goldenberger’s shows how a meme figure’s gender can make them especially vulnerable; Ghyslain Raza’s illustrates how minors and children are especially susceptible to cyberbullying if they appear in a meme; and Justine Sacco’s shows that once something goes public its consequences also have to be public.

These examples also show that digital privacy is difficult to navigate, to say the least. There are examples where violations of privacy are clear, such as with Goldenberger and Raza. And there are examples where privacy violations are a bit murkier, such as the use of Dodson’s public news interview and the shaming of Sacco as a result of her racist tweet. And all of these examples point to what Cagle (2019) attributes to our networked society where smartphones and social media are always already a part of us: "Strangershots aren’t produced by individual humans. They’re produced by human actors working with and through a network of other actors, both human and non-human—a network that results in strangershots that millions of people now have access to across any number of other website and social media platforms" (p. 71). Replace “strangershots” with “memes,” and the same idea applies here. So the question becomes, do we even have a right to privacy anymore? Can we expect anything to be private in this networked world? In this part of my talk, I seek to answer these questions by considering public failure and what it might mean to be forgotten.

Goldenberger and Raza have similar stories: awkward adolescents caught being awkward adolescents and put on display for a large digital public. However, each reacted differently. While Goldenberger was understandably creeped out by being stalked, she was overall amused by the whole thing. A few years later in an interview she said that she “never felt unduly embarrassed about her sudden and unexpected celebrity” (quoted in King, 2015). On the other hand, Raza was totally devastated by the spread of his video. He lost many friends and felt completely isolated as his video spread globally without his consent or control.

Several factors could play into why Goldenberger and Raza reacted so differently to the spread of their memetic content, but two big ones are 1) their ages when their memes became widespread, and 2) the authenticity behind the moment of the meme. Raza was a teenager when his video surfaced online; he was still the same age as he was when he filmed it. Understandably, he would have been unnerved and embarrassed that the whole world saw him in what he considered to be a private moment. However, Goldenberger was in her twenties when the photo resurfaced and became a meme. More than a decade had passed since it had been taken, so she was able to more easily detach her real-life identity from the image in the Ermahgerd meme. Maturity and distance would allow Goldenberger to laugh at her memetic fame, while youth and closeness would make Raza uncomfortable with his.

Furthermore, whereas Raza was performing a kind of play-acting by pretending to be a Jedi, we have no way of knowing how seriously he took that performance. Although he has spoken out against cyberbullying, he has said little about his experience filming his play-acting. On the other hand, we know that the although Goldenberger’s picture appears to capture what one journalist described as “the real, paroxysmal excitement of a little girl at precisely the right millisecond” (King, 2015), it is actually also play-acting. She and her friends used to dress in costumes or strange combinations of clothing and create characters. In the Ermahgerd photo, Goldenberger is in character as “Pervy Dale.” What’s even more interesting is that she wasn’t even a fan of Goosebumps. The books just happened to be nearby and seemed to fit the character at the time. King (2015) points out that “if the photo had been an authentic depiction of an authentic moment—an actual artifact from her awkward tween years—she may have felt different[ly]” about her photo appearing online without her permission. However, because it was a character that she was already displaying in front of a group of her friends (King, 2015), she was able to laugh at it. But Raza’s play-acting may have been a more genuine part of his identity, which may contribute to his unease and humiliation at the world having seen it. Children and adolescents engage in similar play-acting to Raza’s and Goldenberger’s, but it is often meant to remain private.

But even beyond emotional or psychological effects, Garsd (2015) argues that these memes become potentially harmful for their professional lives, much like in the case with Sacco’s racist tweet. She explains, “people’s reputations are involved here. It does very likely impact… people’s ability to find a job.” In Sacco’s case, users may be pleased to hear that she has been fired, but Garsd (2015) points out that that these memes could act as potentially incriminating evidence against meme celebrities like Goldenberger or Raza. Especially now that their names have been connected to the memes in published articles, a quick Google search will reveal their connection to memetic celebrity status. The same goes for Antoine Dodson, who is also connected to not only the original news story, but also the memetic remix, and his attempts to capitalize on them. As the popular adage goes, “the internet never forgets.”

And since the internet never forgets, it also never allows users to fully overcome their public “failures,” and being able to fail in private is part of how we grow and develop our identities. Woodrow Hartzog, a law professor specializing in privacy and obscurity, argues that “It’s important for us to fail when we’re young… That’s how we develop our sense of right and wrong. That’s how we develop our sense of empathy. And the ability to move past that, and not have those same things haunt you.” David Hoffman argues that it’s important to be able to make mistakes in the private sphere so that individuals can learn how to take risks and try new things. Garsd also explains, “it's hard to imagine the mortification of having our silliest teenage moments live on forever.” But that’s what has happened to meme celebrities like Goldenberger and Raza. Even though Goldenberger’s awkward adolescence is over, the meme is still a remnant of a less-refined version of herself that she would have rather kept private. Turning young people into memes is taking away their ability to be youthful, particularly when images and videos of young people like Raza are memed while they are still young. The Star Wars Kid meme took away Raza’s ability to fail, or do something awkward and immature, and grow in private. Instead, he “failed” and the whole world saw.

I would also argue that it’s important to be able to fail even when we’re adults, but our connected digital world does not provide us many opportunities to do so. You can delete a post—as Sacco did—but screencaps last forever. While Dodson lucked out and his memetic celebrity has seemed to benefit him more than harm him, it’s not clear that the same is true for other autotuned remix meme figures. The same goes for Goldenberger and Raza, who have not commented on how their memetic status has affected the way they operate in the world. And we know that Sacco is back working for essentially the same company, but it’s not clear how her day-to-day life has been impacted. Regardless, it’s important to remember that none of these memetic celebrities asked for their images and names to be posted online and turned into memes. Even in the case of Dodson, who was initially not consulted about the use of his interview in the first iteration of the “Bed Intruder” video, each’s likeness was appropriated without their knowledge or permission.

Even the most careful of Internet users can find their information, names, and photos in strange corners of the web. When was the last time you Googled your name? You might be surprised by how much of your information is out there. It is extremely difficult for Internet users to take total control of their digital presence, or for them to determine their own privacy. Websites are constantly tracing us across the internet and feeding the metrics back to developers. Algorithms watch our behavioral patterns and adapt to provide us content they think we want to see. Bots and scrapers are constantly crawling through the internet and compiling results on our personal details on sites like Pipl and White Pages. Our images could show up in a meme or our names could be attached to viral social media posts and we wouldn’t be able to do anything about it.

The main issue is that most countries do not have much legal precedent or statute to protect people from such unsolicited or unwitting reproduction of their image and videos. There is no way, from a legal standpoint, to reclaim and remove these memes from the Internet. Garsd (2015) explains that the European Union and Argentina have implemented “the right to be forgotten,” which “allows for individuals living in these places to ask search engines like Google to de-index certain pages that are irrelevant, false or not newsworthy.” However, Selinger and Hartzog (2014) clarify that this law is less about being “forgotten” because people’s memories can outlast Google indexing. Instead, they prefer the term “right to obscurity” as a way to secure data safety, meaning, "Obscurity is the idea that when information is hard to obtain or understand, it is, to some degree, safe. Safety, here, doesn't mean inaccessible. Competent and determined data hunters armed with the right tools can always find a way to get it. Less committed folks, however, experience great effort as a deterrent" (Selinger and Hartzog, 2014). In other words, there is no way to ensure complete privacy when Google de-indexes content. EU citizens have the ability to reclaim some of the privacy that the internet in general and meming in particular can take away from them, but there is still a risk of undesirable information being found by data hunters.

However, even this imperfect protection is not available on a global scale, and certainly not in the United States where any such attempt to take control of memetic spread could be seen as a first amendment restriction (Sampson, 2013). The closest equivalent is the “eraser button” law in California, which, as Brill describes “requires operators of online services to allow minors to remove content that they posted on the service” (quoted in Selinger and Hartzog, 2014) But even this is imperfect because, like with the “right to be forgotten,” it does not erase the memory of the post nor does it cover screencaps or shares of it. During her time as an FTC commissioner, Brill argued for more tools to be available to everyday users to take better control of their obscurity, but without legislation, the FTC is ultimately limited in its ability to legally enforce it (Selinger and Hartzog, 2014).

These examples also show that digital privacy is difficult to navigate, to say the least. There are examples where violations of privacy are clear, such as with Goldenberger and Raza. And there are examples where privacy violations are a bit murkier, such as the use of Dodson’s public news interview and the shaming of Sacco as a result of her racist tweet. And all of these examples point to what Cagle (2019) attributes to our networked society where smartphones and social media are always already a part of us: "Strangershots aren’t produced by individual humans. They’re produced by human actors working with and through a network of other actors, both human and non-human—a network that results in strangershots that millions of people now have access to across any number of other website and social media platforms" (p. 71). Replace “strangershots” with “memes,” and the same idea applies here. So the question becomes, do we even have a right to privacy anymore? Can we expect anything to be private in this networked world? In this part of my talk, I seek to answer these questions by considering public failure and what it might mean to be forgotten.

Goldenberger and Raza have similar stories: awkward adolescents caught being awkward adolescents and put on display for a large digital public. However, each reacted differently. While Goldenberger was understandably creeped out by being stalked, she was overall amused by the whole thing. A few years later in an interview she said that she “never felt unduly embarrassed about her sudden and unexpected celebrity” (quoted in King, 2015). On the other hand, Raza was totally devastated by the spread of his video. He lost many friends and felt completely isolated as his video spread globally without his consent or control.

Several factors could play into why Goldenberger and Raza reacted so differently to the spread of their memetic content, but two big ones are 1) their ages when their memes became widespread, and 2) the authenticity behind the moment of the meme. Raza was a teenager when his video surfaced online; he was still the same age as he was when he filmed it. Understandably, he would have been unnerved and embarrassed that the whole world saw him in what he considered to be a private moment. However, Goldenberger was in her twenties when the photo resurfaced and became a meme. More than a decade had passed since it had been taken, so she was able to more easily detach her real-life identity from the image in the Ermahgerd meme. Maturity and distance would allow Goldenberger to laugh at her memetic fame, while youth and closeness would make Raza uncomfortable with his.

Furthermore, whereas Raza was performing a kind of play-acting by pretending to be a Jedi, we have no way of knowing how seriously he took that performance. Although he has spoken out against cyberbullying, he has said little about his experience filming his play-acting. On the other hand, we know that the although Goldenberger’s picture appears to capture what one journalist described as “the real, paroxysmal excitement of a little girl at precisely the right millisecond” (King, 2015), it is actually also play-acting. She and her friends used to dress in costumes or strange combinations of clothing and create characters. In the Ermahgerd photo, Goldenberger is in character as “Pervy Dale.” What’s even more interesting is that she wasn’t even a fan of Goosebumps. The books just happened to be nearby and seemed to fit the character at the time. King (2015) points out that “if the photo had been an authentic depiction of an authentic moment—an actual artifact from her awkward tween years—she may have felt different[ly]” about her photo appearing online without her permission. However, because it was a character that she was already displaying in front of a group of her friends (King, 2015), she was able to laugh at it. But Raza’s play-acting may have been a more genuine part of his identity, which may contribute to his unease and humiliation at the world having seen it. Children and adolescents engage in similar play-acting to Raza’s and Goldenberger’s, but it is often meant to remain private.

But even beyond emotional or psychological effects, Garsd (2015) argues that these memes become potentially harmful for their professional lives, much like in the case with Sacco’s racist tweet. She explains, “people’s reputations are involved here. It does very likely impact… people’s ability to find a job.” In Sacco’s case, users may be pleased to hear that she has been fired, but Garsd (2015) points out that that these memes could act as potentially incriminating evidence against meme celebrities like Goldenberger or Raza. Especially now that their names have been connected to the memes in published articles, a quick Google search will reveal their connection to memetic celebrity status. The same goes for Antoine Dodson, who is also connected to not only the original news story, but also the memetic remix, and his attempts to capitalize on them. As the popular adage goes, “the internet never forgets.”

And since the internet never forgets, it also never allows users to fully overcome their public “failures,” and being able to fail in private is part of how we grow and develop our identities. Woodrow Hartzog, a law professor specializing in privacy and obscurity, argues that “It’s important for us to fail when we’re young… That’s how we develop our sense of right and wrong. That’s how we develop our sense of empathy. And the ability to move past that, and not have those same things haunt you.” David Hoffman argues that it’s important to be able to make mistakes in the private sphere so that individuals can learn how to take risks and try new things. Garsd also explains, “it's hard to imagine the mortification of having our silliest teenage moments live on forever.” But that’s what has happened to meme celebrities like Goldenberger and Raza. Even though Goldenberger’s awkward adolescence is over, the meme is still a remnant of a less-refined version of herself that she would have rather kept private. Turning young people into memes is taking away their ability to be youthful, particularly when images and videos of young people like Raza are memed while they are still young. The Star Wars Kid meme took away Raza’s ability to fail, or do something awkward and immature, and grow in private. Instead, he “failed” and the whole world saw.

I would also argue that it’s important to be able to fail even when we’re adults, but our connected digital world does not provide us many opportunities to do so. You can delete a post—as Sacco did—but screencaps last forever. While Dodson lucked out and his memetic celebrity has seemed to benefit him more than harm him, it’s not clear that the same is true for other autotuned remix meme figures. The same goes for Goldenberger and Raza, who have not commented on how their memetic status has affected the way they operate in the world. And we know that Sacco is back working for essentially the same company, but it’s not clear how her day-to-day life has been impacted. Regardless, it’s important to remember that none of these memetic celebrities asked for their images and names to be posted online and turned into memes. Even in the case of Dodson, who was initially not consulted about the use of his interview in the first iteration of the “Bed Intruder” video, each’s likeness was appropriated without their knowledge or permission.

Even the most careful of Internet users can find their information, names, and photos in strange corners of the web. When was the last time you Googled your name? You might be surprised by how much of your information is out there. It is extremely difficult for Internet users to take total control of their digital presence, or for them to determine their own privacy. Websites are constantly tracing us across the internet and feeding the metrics back to developers. Algorithms watch our behavioral patterns and adapt to provide us content they think we want to see. Bots and scrapers are constantly crawling through the internet and compiling results on our personal details on sites like Pipl and White Pages. Our images could show up in a meme or our names could be attached to viral social media posts and we wouldn’t be able to do anything about it.

The main issue is that most countries do not have much legal precedent or statute to protect people from such unsolicited or unwitting reproduction of their image and videos. There is no way, from a legal standpoint, to reclaim and remove these memes from the Internet. Garsd (2015) explains that the European Union and Argentina have implemented “the right to be forgotten,” which “allows for individuals living in these places to ask search engines like Google to de-index certain pages that are irrelevant, false or not newsworthy.” However, Selinger and Hartzog (2014) clarify that this law is less about being “forgotten” because people’s memories can outlast Google indexing. Instead, they prefer the term “right to obscurity” as a way to secure data safety, meaning, "Obscurity is the idea that when information is hard to obtain or understand, it is, to some degree, safe. Safety, here, doesn't mean inaccessible. Competent and determined data hunters armed with the right tools can always find a way to get it. Less committed folks, however, experience great effort as a deterrent" (Selinger and Hartzog, 2014). In other words, there is no way to ensure complete privacy when Google de-indexes content. EU citizens have the ability to reclaim some of the privacy that the internet in general and meming in particular can take away from them, but there is still a risk of undesirable information being found by data hunters.

However, even this imperfect protection is not available on a global scale, and certainly not in the United States where any such attempt to take control of memetic spread could be seen as a first amendment restriction (Sampson, 2013). The closest equivalent is the “eraser button” law in California, which, as Brill describes “requires operators of online services to allow minors to remove content that they posted on the service” (quoted in Selinger and Hartzog, 2014) But even this is imperfect because, like with the “right to be forgotten,” it does not erase the memory of the post nor does it cover screencaps or shares of it. During her time as an FTC commissioner, Brill argued for more tools to be available to everyday users to take better control of their obscurity, but without legislation, the FTC is ultimately limited in its ability to legally enforce it (Selinger and Hartzog, 2014).

Toward a Heuristic for an Ethic of Use for Privacy

While there is no legal “right to be forgotten” or “right to obscurity” in the United States, it seems to me that memers—both producers and consumers who share memes—could be more conscious of their memetic creations by practicing an ethic of use that incorporates considerations of privacy. I do not mean to suggest that it should be as stringent as the European Union’s “meme ban” from 2018. Such legislation has not quite killed off memetic creation in Europe, but it has made it unproductively more difficult under the guise of copyright and intellectual property protection. I also do not mean to suggest that something like a memetic right to obscurity would be legally enforceable. Like Brad Kim said in his Q&A, it would be incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to enforce such a law in digital spaces without censorship and control akin to China’s.

As such, I want to close my talk tonight by positing an ethical heuristic of meming that includes a series of questions aimed at helping users determine if creating or sharing a particular meme might be a violation of privacy. Here I provide a few guiding questions, although there are certainly others that would also be appropriate. Some of these are adapted from David Hoffman’s (2013) taxonomy of reasons a person might reasonably request legally backed obscurity.

In an ideal world, memers could follow this heuristic when creating and sharing memes. Unfortunately, we obviously do not live in an ideal world and I realize that my goals here are lofty. The ones most likely to meme ethically are the ones who were probably already being careful and conscientious in their meming, while those who intentionally meme maliciously will continue to do so. But there are those who may have been unintentionally or uncritically meming maliciously, and those are the ones I think will be the most likely to change their meming habits to be more aware of ethical privacy concerns. And I hope that many of us in this room fall into this category. My immediate goal from tonight’s talk is that those of you who create and/or share memes will be conscientious of privacy and obscurity as you continue to do so.

As such, I want to close my talk tonight by positing an ethical heuristic of meming that includes a series of questions aimed at helping users determine if creating or sharing a particular meme might be a violation of privacy. Here I provide a few guiding questions, although there are certainly others that would also be appropriate. Some of these are adapted from David Hoffman’s (2013) taxonomy of reasons a person might reasonably request legally backed obscurity.

- Was the content intended to be public or to circulate beyond an immediate network? Images and videos may be sent to specific people, found on devices without permission, recorded surreptitiously, or shared in larger publics beyond an intended circle of recipients.

- Does the content include a depiction of a person in a compromising situation? Some memetic images and videos rely on shaming people for their humor.

- Does the content exploit an identity characteristic? Some memetic images and videos hinge on representations of race, gender, ability, sexuality, appearance, or other intersecting identity markers for their punchline.

- How old is the person depicted in the content? Some memetic media contains images of minors acquired without their consent or knowledge.

- Does the content include a person’s real name or username? Many screencaps of social media posts include content that could damage a person’s reputation by virtue of being attached to a real name or username that could easily be traced to the user.

- Does the content include other sensitive information? This could include locative indicators (address, street signs, and other unique markers of a person’s location) and other information a person might reasonably expect to be kept private.

- Could someone’s real life be negatively impacted by appearing in a meme or circulating in a screencap? Not all memetic content presents its subjects in a negative light, but special consideration should be taken for that which does.

In an ideal world, memers could follow this heuristic when creating and sharing memes. Unfortunately, we obviously do not live in an ideal world and I realize that my goals here are lofty. The ones most likely to meme ethically are the ones who were probably already being careful and conscientious in their meming, while those who intentionally meme maliciously will continue to do so. But there are those who may have been unintentionally or uncritically meming maliciously, and those are the ones I think will be the most likely to change their meming habits to be more aware of ethical privacy concerns. And I hope that many of us in this room fall into this category. My immediate goal from tonight’s talk is that those of you who create and/or share memes will be conscientious of privacy and obscurity as you continue to do so.

References

Baio, A. (2003, July 16). Shipping the Star Wars Kid’s presents. Waxy. Retrieved from http://waxy.org/2003/07/shipping_the_st/

Brown, James J., Jr. (2015). Ethical programs: Hospitality and the rhetorics of software. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Retrieved from https://www.press.umich.edu/8305860/ethical_programs

Cagle, Lauren E. (2019). Surveilling strangers: The disciplinary biopower of digital genre assemblages. Computers and Composition, 52, 67-78.

Ellis, Emma G. (2017). Whatever your side, doxing in a perilous form of justice. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/doxing-charlottesville/

Garsd, Jasmine. (2015, March 3). Internet memes and the ‘right to be forgotten.’ NPR: All Tech Considered. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2015/03/03/390463119/internet-memes-and-the-right-to-be-forgotten

Hoffman, David. (2013). How obscurity could help the right to fail. Policy@Intel. Retrieved from https://blogs.intel.com/policy/2013/03/29/how-obscurity-could-help-the-right-to-fail/#gs.wm6y0z

Johnson, Victoria. (2018). Justine Sacco, who was fired from IAC for controversial “AIDS” tweet, basically got her old job back. Complex. Retrieved from https://www.complex.com/life/2018/01/justine-sacco-got-her-job-back-iac

King, Darryn. (2015). Ermahgerddon: The untold story of the Ermahgerd girl. Vanity Fair. Retrieved from https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2015/10/ermahgerd-girl-true-story

Knobel, Michelle & Lankshear, Colin. (2007). Online memes, affinities, and cultural production. In M. Knobel & C. Lankshear (Eds.) A new literacy sampler (pp. 197-227). New York: Peter Lang.

Know Your Meme (2010). Antoine Dodson / Bed intruder. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/antoine-dodson-bed-intruder

Know Your Meme (2011). Eccentric witness lady / Backin’ up. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/eccentric-witness-lady-backin-up

Know Your Meme (2012a). Ermahgerd. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/ermahgerd

Know Your Meme (2012b). Sweet Brown / Ain’t nobodoy got time for that. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/sweet-brown-aint-nobody-got-time-for-that

Know Your Meme (2013). Daym Drops. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/people/daym-drops

Know Your Meme (2016). Michelle Dobyne / It’s poppin / No fire, not today. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/michelle-dobyne-it-s-poppin-no-fire-not-today

Know Your Meme (2018). Q&A with Brad Kim, Janitor-in-Chieef of Know Your Meeme. Facebook. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/knowyourmeme/videos/291188088201762/

Maclean’s. (2013). 10 years later, ‘Star Wars Kid’ speaks out. Maclean’s. Retrieved from https://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/10-years-later-the-star-wars-kid-speaks-out/

Miller, Leila. (2018). How we identified white supremacists after Charlottesville. Frontline. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/how-we-identified-white-supremacists-after-charlottesville/

Porter, James E. (1998). Rhetorical ethics and internetworked writing. Greenwich, CT: Ablex.

Ronson, Jon (2015). How one stupid tweet blew up Justine Sacco’s life. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/15/magazine/how-one-stupid-tweet-ruined-justine-saccos-life.html

Scott, Sydney. (2018). Antoine Dodson Is Giving Back To His Community Following Fame After The “Bed Intruder Song.” Essence Retrieved from https://www.essence.com/celebrity/antoine-dodson-bed-intruder-song-after-internet-fame/

Selfe, Cynthia L. & Selfe, Richard J., Jr. (1994). The politics of the interface. College Composition and Communication, 45(4), 480-504.

Selinger, Evan & Hartzog, Woodrow. (2014). Google can’t forget you, but it should make you hard to find. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2014/05/google-cant-forget-you-but-it-should-make-you-hard-to-find/

Selinger, Evan & Hartzog, Woodrow. (2015). Why you have the right to obscurity. CS Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Passcode/Passcode-Voices/2015/0415/Why-you-have-the-right-to-obscurity

Sparby, Erika M. (2017). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric in 4chan’s collective identity. Computers and Composition, 45, 85–97.

Williams, Rev. Charles E. II. (2013). I Am Charles Ramsey and Sweet Brown: “You do what you have to do” and “Aint nobody got time for dat.” Huffington Post. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/i-am-charles-ramsey-and-s_b_3248502

Brown, James J., Jr. (2015). Ethical programs: Hospitality and the rhetorics of software. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Retrieved from https://www.press.umich.edu/8305860/ethical_programs

Cagle, Lauren E. (2019). Surveilling strangers: The disciplinary biopower of digital genre assemblages. Computers and Composition, 52, 67-78.

Ellis, Emma G. (2017). Whatever your side, doxing in a perilous form of justice. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/doxing-charlottesville/

Garsd, Jasmine. (2015, March 3). Internet memes and the ‘right to be forgotten.’ NPR: All Tech Considered. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2015/03/03/390463119/internet-memes-and-the-right-to-be-forgotten

Hoffman, David. (2013). How obscurity could help the right to fail. Policy@Intel. Retrieved from https://blogs.intel.com/policy/2013/03/29/how-obscurity-could-help-the-right-to-fail/#gs.wm6y0z

Johnson, Victoria. (2018). Justine Sacco, who was fired from IAC for controversial “AIDS” tweet, basically got her old job back. Complex. Retrieved from https://www.complex.com/life/2018/01/justine-sacco-got-her-job-back-iac

King, Darryn. (2015). Ermahgerddon: The untold story of the Ermahgerd girl. Vanity Fair. Retrieved from https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2015/10/ermahgerd-girl-true-story

Knobel, Michelle & Lankshear, Colin. (2007). Online memes, affinities, and cultural production. In M. Knobel & C. Lankshear (Eds.) A new literacy sampler (pp. 197-227). New York: Peter Lang.

Know Your Meme (2010). Antoine Dodson / Bed intruder. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/antoine-dodson-bed-intruder

Know Your Meme (2011). Eccentric witness lady / Backin’ up. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/eccentric-witness-lady-backin-up

Know Your Meme (2012a). Ermahgerd. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/ermahgerd

Know Your Meme (2012b). Sweet Brown / Ain’t nobodoy got time for that. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/sweet-brown-aint-nobody-got-time-for-that

Know Your Meme (2013). Daym Drops. Know Your Meme. Retrieved from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/people/daym-drops