Memetic Critical Power Tools: Teaching an Ethic of Privacy and Identity for Memes in the Technical Communication Classroom

It’s been no secret for a while now that digital privacy is a fraught concept. Countless thoughtpieces have drawn readers in with the provocative headline, "is privacy dead?” From backend data collection and circulation to active doxing and other abuses of information, the answer appears to be “mostly, yes.” This presentation, taken from a larger in-progress chapter from my in-progress book called Memetic Rhetorics, begins to posit what an ethical framework for memetic privacy might look like. Given the shorter nature of presentations this year, I don’t have time to formally discuss how to teach it in the tech comm classroom, as my title promises, but I am happy to answer questions about it later.

As Beck and Hutchinson Campos (2021) point out, defining what we mean when we say “privacy” is difficult because of “the utter disharmony in views about the many distinctions of discretion due to varying subject positions and life experiences.” For the sake of simplicity and because it seems to align closely with everyday users’ notion of it, I use Cagle’s (2019) definition of privacy, conceptualizing it “in a more general way to highlight people’s varied expectations of surveillance on the street, in businesses, on college campuses, and across other spaces that range from clearly public to quasi-public to self-evidently private.” I supplement it with former Federal Trade Commissioner Julie Brill’s redefinition of privacy for the digital age. She says, "individuals cherish being connected, shopping online and through apps, and sharing with friends and colleagues through social networks, but believe that their online activities shouldn’t be subject to invasive monitoring… I think the meaning of privacy now also includes an individual’s right to have some control over their online persona and destiny" (qtd. Selinger & Hartzog, 2015). Privacy, then, is an expected ability to move through spaces and perform activities without being surveilled as well as to control how they are presented in digital spaces.

Memes are important visual texts to study because they are photos or images that are taken up and altered in some way as they move and circulate through spaces; in fact it is this alteration, or remix, that distinguishes memes from any other kind of content, including viral content. As they move through networks, they may acquire new text, or the same text may be put on a new image, or the image itself may be changed via Photoshop… the possibilities for change are as endless as memers’ imaginations. A lot of memes stay pretty localized within the networks that share and circulate them, but every so often memes are able to transcend networks and circulate beyond, gaining a wide audiences and sometimes national attention.

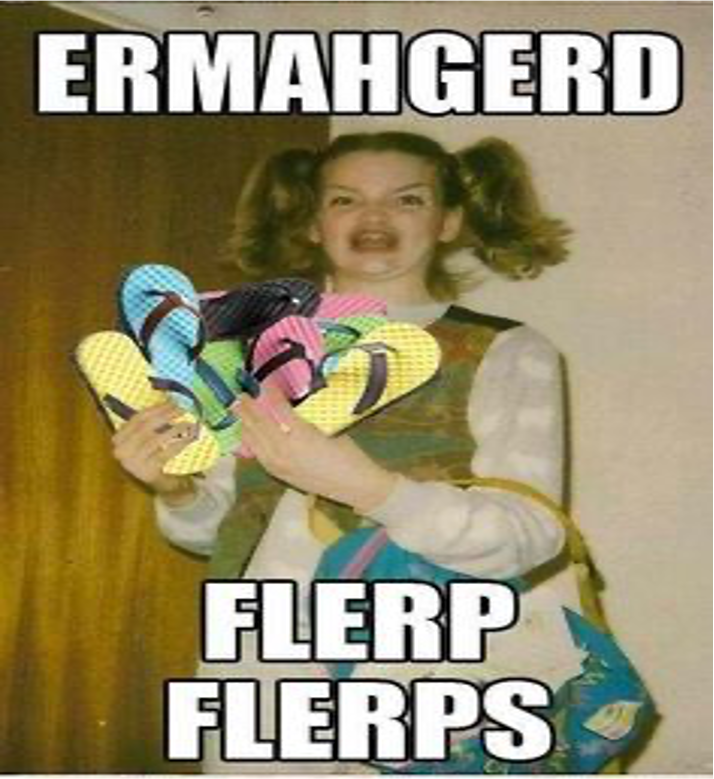

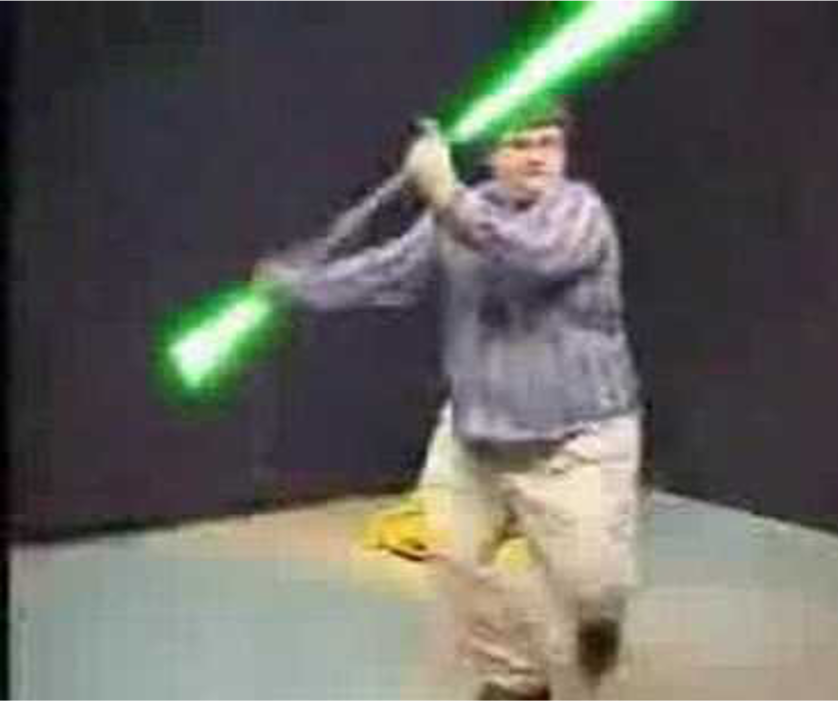

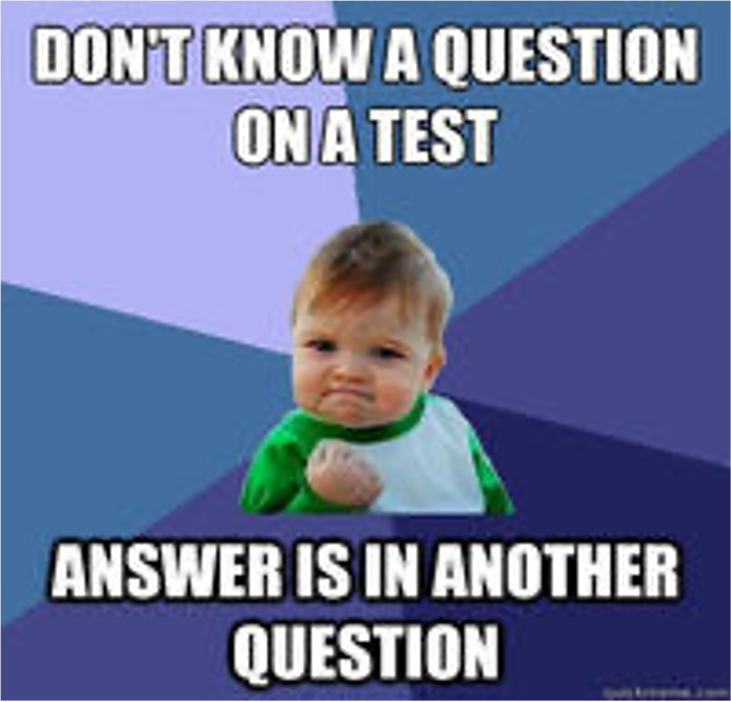

But, as Dieterle, Edwards, and Martin (2020) point out, “sharing is not always caring—indeed, sharing can cause harm to individuals, communities, and publics.” They talk about resharing content as a rhetorical, world-building act that has consequences beyond the platforms on which they are shared. Because memes can circulate private and identifying information in social media spaces, they exist at the nexus of data and privacy. The unwitting fame that results from having a photo or name circulate as part of a meme can have a huge impact on the figure’s or user’s life. In the larger chapter I’m working on, I present a number of extensive examples to show the many identity and privacy implications for meming without permission, highlighting Antoine Dodson’s “Bed Intruder” moment, Maggie Goldenberger’s appearance as “Ermahgerd,” Ghyslain Raza’s unwanted attention as “Star Wars Kid,” and Sammy Griner’s fame as “Success Kid.” For the sake of time, I’m going to highlight the key points really quickly here.

As Beck and Hutchinson Campos (2021) point out, defining what we mean when we say “privacy” is difficult because of “the utter disharmony in views about the many distinctions of discretion due to varying subject positions and life experiences.” For the sake of simplicity and because it seems to align closely with everyday users’ notion of it, I use Cagle’s (2019) definition of privacy, conceptualizing it “in a more general way to highlight people’s varied expectations of surveillance on the street, in businesses, on college campuses, and across other spaces that range from clearly public to quasi-public to self-evidently private.” I supplement it with former Federal Trade Commissioner Julie Brill’s redefinition of privacy for the digital age. She says, "individuals cherish being connected, shopping online and through apps, and sharing with friends and colleagues through social networks, but believe that their online activities shouldn’t be subject to invasive monitoring… I think the meaning of privacy now also includes an individual’s right to have some control over their online persona and destiny" (qtd. Selinger & Hartzog, 2015). Privacy, then, is an expected ability to move through spaces and perform activities without being surveilled as well as to control how they are presented in digital spaces.

Memes are important visual texts to study because they are photos or images that are taken up and altered in some way as they move and circulate through spaces; in fact it is this alteration, or remix, that distinguishes memes from any other kind of content, including viral content. As they move through networks, they may acquire new text, or the same text may be put on a new image, or the image itself may be changed via Photoshop… the possibilities for change are as endless as memers’ imaginations. A lot of memes stay pretty localized within the networks that share and circulate them, but every so often memes are able to transcend networks and circulate beyond, gaining a wide audiences and sometimes national attention.

But, as Dieterle, Edwards, and Martin (2020) point out, “sharing is not always caring—indeed, sharing can cause harm to individuals, communities, and publics.” They talk about resharing content as a rhetorical, world-building act that has consequences beyond the platforms on which they are shared. Because memes can circulate private and identifying information in social media spaces, they exist at the nexus of data and privacy. The unwitting fame that results from having a photo or name circulate as part of a meme can have a huge impact on the figure’s or user’s life. In the larger chapter I’m working on, I present a number of extensive examples to show the many identity and privacy implications for meming without permission, highlighting Antoine Dodson’s “Bed Intruder” moment, Maggie Goldenberger’s appearance as “Ermahgerd,” Ghyslain Raza’s unwanted attention as “Star Wars Kid,” and Sammy Griner’s fame as “Success Kid.” For the sake of time, I’m going to highlight the key points really quickly here.

|

In 2010, Dodson’s remarks from a news interview when he was clearly flustered went viral when YouTuber’s The Gregory Brothers remixed his famous line—“hide yo’ kids, hide yo’ wife, hide yo’ husbands, ‘cuz they rapin’ everybody up in here”—into an autotuned song. Several other similar remixes followed in the years after, and they all had one commonality: they featured Black and/or disabled people in moments of crisis, highlighting one key line and inviting viewers to laugh at them and their use of AAVE. The Gregory Brothers—all white and seemingly able-bodied with audiences of a similar demographic—have seen great financial success from these videos.

|

|

In 2015, a photo of Goldenberger as an adolescent surfaced on reddit and users began adding text meant to imitate what they called “retainer lisp.” The meme itself is ableist in its depiction of a speech impediment, but the biggest danger came a few months later when users on 4chan tracked down Goldenberger and identified her as the meme figure. She later found out that she had been stalked by an anonymous bounty hunter while on vacation when photos of herself wearing a bikini surfaced online.

|

|

In 2002, 14-year-old Raza used his high school’s AV room and equipment to record himself pretending to be a Jedi fighting invisible enemies with a light saber (using what appears to be a metal pole). He forgot to take the tape out before he left, and other students found Raza’s recording a few months later and posted it online. This meme has been remixed countless times across mainstream and underground media. Raza was both bullied by his classmates and cyberbullied online; he dropped out of school to receive mental health aid.

|

|

In 2007, Laney Griner uploaded to Flickr a photo of her 11-month-old son, Sammy, holding a fistful of sand on the beach. Although she posted it to her personal Flickr channel, the dubious nature of privacy settings on social media sites left the image open to be viewed by users beyond her known circle; shortly after, “Success Kid” was born. Now a teenager, Griner has used his memetic fame to help his family, raising money for his father’s life-saving treatment. However, because of the meme and his fundraising, his entire life he has dealt with people approaching him on the street to ask him to do the pose and take selfies.

|

I went through these four examples quickly, but they show a range of memetic privacy violations: Dodson was exploited for capitalist gain in a sort of minstrel show, Goldenberger was stalked in real life and online, Raza had to seek mental health care because of his traumatic experience, and Griner is approached on the street regularly. Importantly, Raza was a minor when Star Wars Kid was at its peak, and Griner still is; they were children who became meme famous before they were even able to fully conceptualize what “privacy” might mean.

While we often look at memes like these and see them as harmless good fun and humor, these four examples show that this is not always the case for the people who appear in them. These are real people, and their being memed has real consequences on their lives. As such, it is crucial to develop an ethical memetic framework for privacy when meming. Keeping in line with a long line of scholars, I see ethical frameworks like these not as hard and fast rules, but as general guidelines that we can use, adapt, disregard, and add to as fits the contexts and circumstances of each unique situation (DeVoss and Porter, 2006; Coley, 2011; Brown, 2015; Sparby, 2017; Reyman & Sparby, 2020). In Memetic Rhetorics, I have taken steps toward this framework through seven questions, some of which I have adapted from David Hoffman’s (2013) taxonomy of reasons a person might reasonably request legally backed obscurity; some are also inspired by Dieterle, Edwards, and Martin’s (2020) guiding questions toward an ethics of recirculation.

1. Was the content intended to be public or to circulate beyond an immediate network?

2. Does the content include a depiction of a person in a compromising situation, or could its circulation put someone in a compromised position?

3. Does the content exploit an identity characteristic as a punchline?

4. How old is the person depicted in the content?

5. Does the content include a person’s real name or username?

6. Does the content include other sensitive information?

7. Could someone’s real life be negatively and unproductively impacted by appearing in a meme or circulating in a screencap?

These seven questions are only the start of an ethical framework for memes and privacy. Some key aspects with which I have not yet grappled here include the intersections of privacy and celebrity, privacy and copyright, privacy and positive representations, and so many more that need examination. But I hope that this framework can get us thinking about how to meme ethically with regards to privacy, and especially how to use these mundane visual texts that appear everywhere as ways to teach students about the importance of privacy.

References

Beck, Estee & Hutchinson Campos, Les. (2021). Introduction. In Beck, Estee & Hutchinson Campos, Les (eds.) Privacy matters: Conversations about surveillance within and beyond the classroom (pp. 3-14). Louisville: University of Colorado Press.

Brown, James J., Jr. (2015). Ethical programs: Hospitality and the rhetorics of software. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Cagle, L. E. (2019). Surveilling strangers: The disciplinary biopower of digital genre assemblages. Computers and Composition, 52, 67-78.

Coley, Toby. (Ed.). (2011). Computers and Composition Online. Retrieved from http://cconlinejournal.org/fall2011.html

DeVoss, Danielle N., & Porter, James E. (2006). Why Napster matters to writing: Filesharing as new ethic of digital delivery. Computers and Composition, 23, pp. 178-210.

Dieterle, Brandy, Edwards, Dustin, and Martin, Paul “Dan.” (2020). Confronting digital aggression with an ethics of circulation. In Reyman, Jessica & Sparby, Erika M. (Eds.) Digital ethics: Rhetoric and responsibility in online aggression (pp. 197-213). New York, Routledge.

Hoffman, David. (2013). How obscurity could help the right to fail. Policy@Intel. Retrieved from https://blogs.intel.com/policy/2013/03/29/how-obscurity-could-help-the-right-to-fail/#gs.wm6y0z

Reyman, Jessica & Sparby, Erika M. Introduction: Toward an ethic of responsibility in digital aggression. In Reyman, Jessica & Sparby, Erika M. (eds.) Digital ethics: Rhetoric and responsibility in online aggression (pp. 1-14). New York, Routledge.

Selinger, Evan & Hartzog, Woodrow. (2015). Why you have the right to obscurity. CS Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Passcode/Passcode-Voices/2015/0415/Why-you-have-the-right-to-obscurity

Sparby, Erika M. (2017). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric in 4chan’s collective identity. Computers and Composition, 45, 85–97.

While we often look at memes like these and see them as harmless good fun and humor, these four examples show that this is not always the case for the people who appear in them. These are real people, and their being memed has real consequences on their lives. As such, it is crucial to develop an ethical memetic framework for privacy when meming. Keeping in line with a long line of scholars, I see ethical frameworks like these not as hard and fast rules, but as general guidelines that we can use, adapt, disregard, and add to as fits the contexts and circumstances of each unique situation (DeVoss and Porter, 2006; Coley, 2011; Brown, 2015; Sparby, 2017; Reyman & Sparby, 2020). In Memetic Rhetorics, I have taken steps toward this framework through seven questions, some of which I have adapted from David Hoffman’s (2013) taxonomy of reasons a person might reasonably request legally backed obscurity; some are also inspired by Dieterle, Edwards, and Martin’s (2020) guiding questions toward an ethics of recirculation.

1. Was the content intended to be public or to circulate beyond an immediate network?

2. Does the content include a depiction of a person in a compromising situation, or could its circulation put someone in a compromised position?

3. Does the content exploit an identity characteristic as a punchline?

4. How old is the person depicted in the content?

5. Does the content include a person’s real name or username?

6. Does the content include other sensitive information?

7. Could someone’s real life be negatively and unproductively impacted by appearing in a meme or circulating in a screencap?

These seven questions are only the start of an ethical framework for memes and privacy. Some key aspects with which I have not yet grappled here include the intersections of privacy and celebrity, privacy and copyright, privacy and positive representations, and so many more that need examination. But I hope that this framework can get us thinking about how to meme ethically with regards to privacy, and especially how to use these mundane visual texts that appear everywhere as ways to teach students about the importance of privacy.

References

Beck, Estee & Hutchinson Campos, Les. (2021). Introduction. In Beck, Estee & Hutchinson Campos, Les (eds.) Privacy matters: Conversations about surveillance within and beyond the classroom (pp. 3-14). Louisville: University of Colorado Press.

Brown, James J., Jr. (2015). Ethical programs: Hospitality and the rhetorics of software. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Cagle, L. E. (2019). Surveilling strangers: The disciplinary biopower of digital genre assemblages. Computers and Composition, 52, 67-78.

Coley, Toby. (Ed.). (2011). Computers and Composition Online. Retrieved from http://cconlinejournal.org/fall2011.html

DeVoss, Danielle N., & Porter, James E. (2006). Why Napster matters to writing: Filesharing as new ethic of digital delivery. Computers and Composition, 23, pp. 178-210.

Dieterle, Brandy, Edwards, Dustin, and Martin, Paul “Dan.” (2020). Confronting digital aggression with an ethics of circulation. In Reyman, Jessica & Sparby, Erika M. (Eds.) Digital ethics: Rhetoric and responsibility in online aggression (pp. 197-213). New York, Routledge.

Hoffman, David. (2013). How obscurity could help the right to fail. Policy@Intel. Retrieved from https://blogs.intel.com/policy/2013/03/29/how-obscurity-could-help-the-right-to-fail/#gs.wm6y0z

Reyman, Jessica & Sparby, Erika M. Introduction: Toward an ethic of responsibility in digital aggression. In Reyman, Jessica & Sparby, Erika M. (eds.) Digital ethics: Rhetoric and responsibility in online aggression (pp. 1-14). New York, Routledge.

Selinger, Evan & Hartzog, Woodrow. (2015). Why you have the right to obscurity. CS Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Passcode/Passcode-Voices/2015/0415/Why-you-have-the-right-to-obscurity

Sparby, Erika M. (2017). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric in 4chan’s collective identity. Computers and Composition, 45, 85–97.