© Erika M. Sparby

When Trolls Become Technical Communicators:

A Case Study of iOS8 and Wave

Adapted from a presentation at ATTW 2018, Kansas City, KS

|

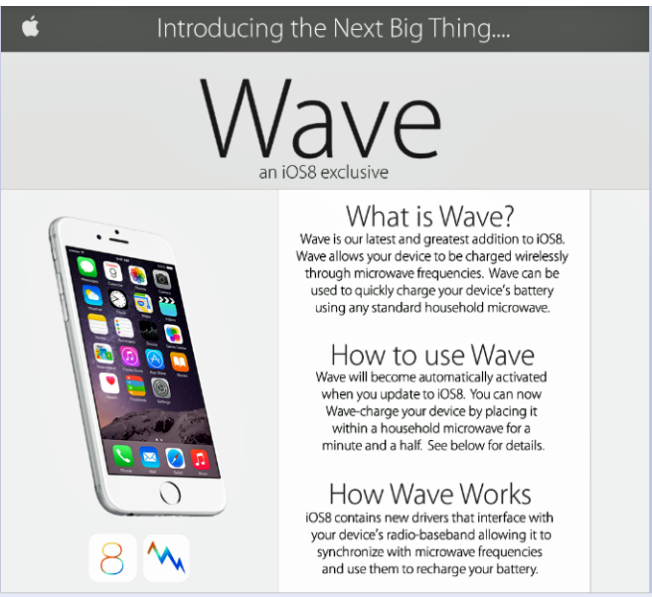

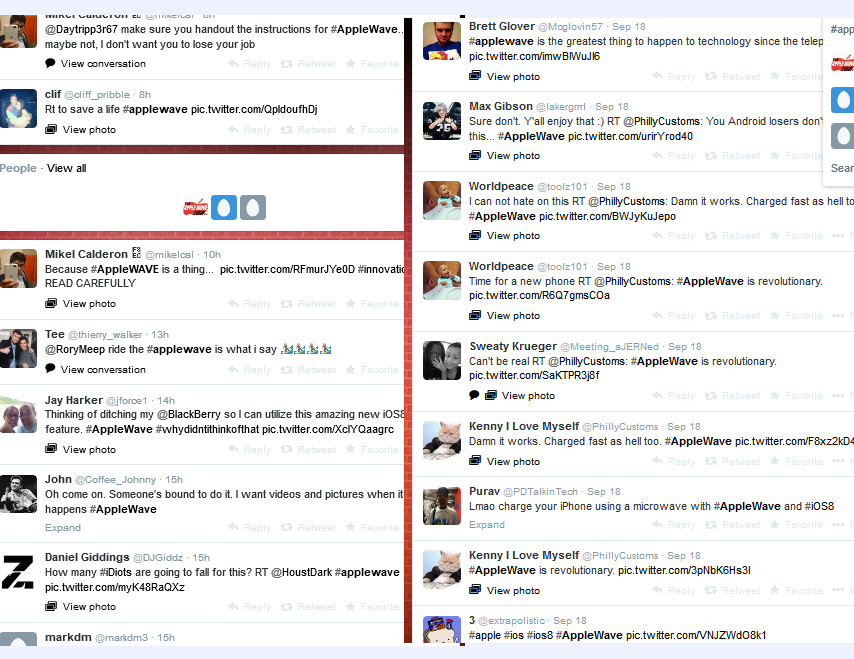

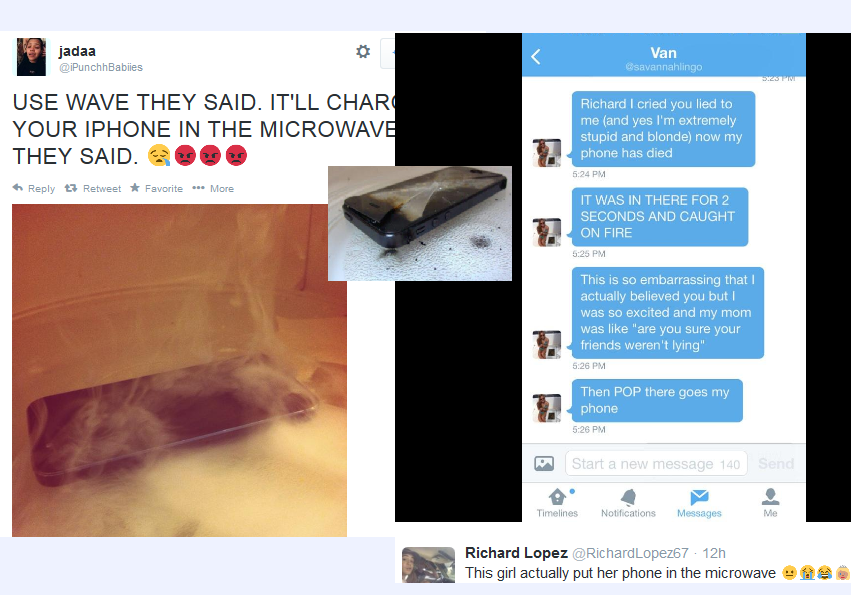

In September 2014, Apple released iOS8 for the iPhone 6. The Apple website and forums, as well as niche blogs and other social media, were abuzz about its most exciting updates. In particular, Twitter began raving about Wave, a new feature that allowed users to microwave their phones to charge them. The promise was utopic. Those in a hurry but with a low battery could microwave their iPhones for a minute and a half and be on their way. But of course, the promise was a lie. I don’t think I need to tell you what happens when metal and magnets meet microwave. Instead, Wave and its documentation were part of a troll raid orchestrated by 4chan.

|

Today I talk about trolls as technical communicators. The Wave feature is not the only time trolls have created documentation aimed at deceiving Apple users: they have also tried to get people to snap their phones in half and to submerge them in water, and there have been previous attempts at something like Wave. Most recently, they also gained some traction with an instructional video that explained how to access the headphone jack on the iPhone 7 by drilling a hole in the bottom. Today I ask and begin answering a question that I think we as a field should grapple with: “What can we learn from trolls who convinced people to nuke their iPhones?” Or, “What can we learn from Internet trolls who are co-opting tech com for deceptive ends?” I turn to tactical technical communication as a way of beginning to make sense of why we need to pay attention to trolls.

First, some quick terminology clarification. 4chan is an online imageboard known as the “Internet Hate Machine,” although this is an oversimplified description. 4chan actually created this image to make fun of people who call them that. There is no central user database, so all posts are anonymous. It was once the homebase for the hacker group Anonymous, and remains one of main gathering places for trolls. When I refer to trolls and trolling, I mean it as a specific set of behaviors differentiated from targeted aggression. Trolling, as Phillips (2015) defines it, is directed generally at a group of people. Trolls bait others with provocative content, wait for someone to respond, and then laugh when someone takes the bait. Some forms of trolling are more aggressive than others, but it is important to distinguish trolling and other aggressive behaviors: calling behaviors like cyberstalking “trolling” trivializes them.

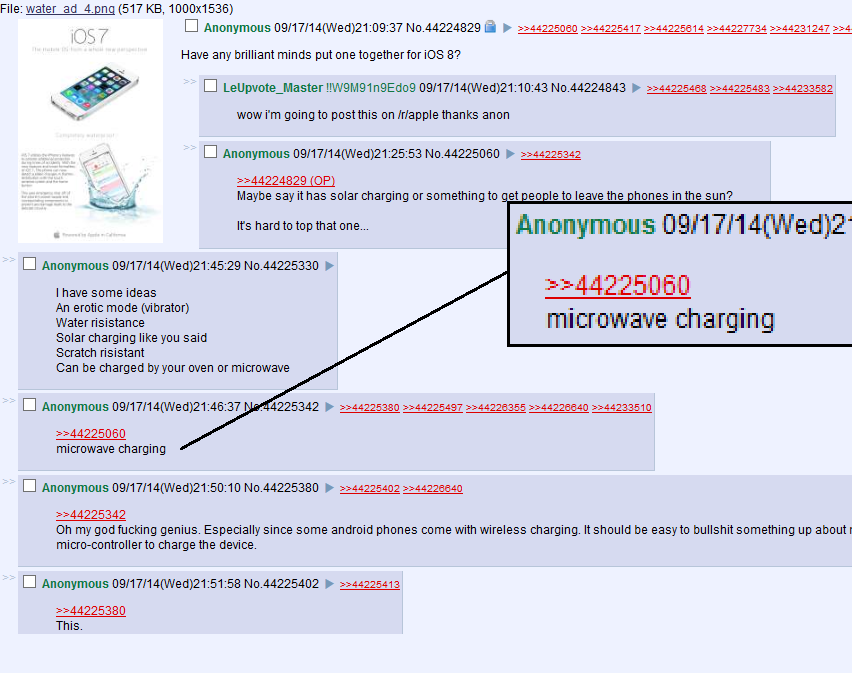

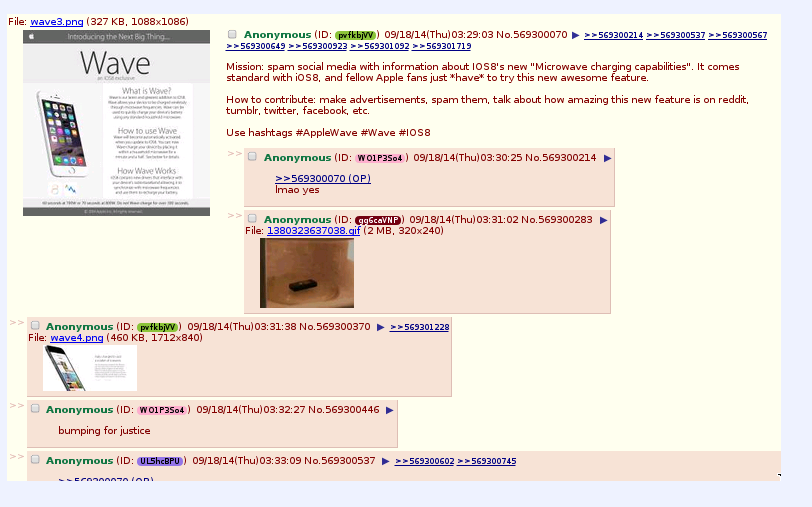

Typically, trolls work alone, infiltrating various corners of the Internet to stir people up. If you’ve been to a comments section on a website for any length of time, you’ve probably seen a troll. But sometimes trolls work together for a larger common goal, which is called a “raid.” 4chan serves as a forum for them to congregate, but be clear, the vast majority of conversations on 4chan are not scheming for the next raid. In fact, one can spend hours there without seeing the inception of any trolling raids. I know this because I clocked hundreds of hours on /b/, one of the most active boards, while working on my dissertation, and I only saw three. One of them was the Wave raid, and the other two were unsuccessful.

Before I turn to tactical technical communication, I want to spend some time looking more closely at this promotional document. At first glance, this document is quite professional, and deliberately so. It matches the minimalist design Apple is known for, and discussions on the board show that the trolls went to great lengths to ensure that they match colors and font styles as closely as possible. The image of the phone matches the teaser image Apple used to promote iOS8 on their website before its launch. Even the wording is deliberate: Apple says iOS8 will be “the biggest release ever,” and the trolls claim Wave is “the next big thing.” Remarkably, the trolls even devised their own Wave app icon that stylistically imitates the “8” in the logo. All of these design choices add to the document’s ethos, convincing some unsuspecting users that Wave is a legitimate feature. If you didn’t know what happens when you microwave a phone, you could probably be convinced that this was real.

First, some quick terminology clarification. 4chan is an online imageboard known as the “Internet Hate Machine,” although this is an oversimplified description. 4chan actually created this image to make fun of people who call them that. There is no central user database, so all posts are anonymous. It was once the homebase for the hacker group Anonymous, and remains one of main gathering places for trolls. When I refer to trolls and trolling, I mean it as a specific set of behaviors differentiated from targeted aggression. Trolling, as Phillips (2015) defines it, is directed generally at a group of people. Trolls bait others with provocative content, wait for someone to respond, and then laugh when someone takes the bait. Some forms of trolling are more aggressive than others, but it is important to distinguish trolling and other aggressive behaviors: calling behaviors like cyberstalking “trolling” trivializes them.

Typically, trolls work alone, infiltrating various corners of the Internet to stir people up. If you’ve been to a comments section on a website for any length of time, you’ve probably seen a troll. But sometimes trolls work together for a larger common goal, which is called a “raid.” 4chan serves as a forum for them to congregate, but be clear, the vast majority of conversations on 4chan are not scheming for the next raid. In fact, one can spend hours there without seeing the inception of any trolling raids. I know this because I clocked hundreds of hours on /b/, one of the most active boards, while working on my dissertation, and I only saw three. One of them was the Wave raid, and the other two were unsuccessful.

Before I turn to tactical technical communication, I want to spend some time looking more closely at this promotional document. At first glance, this document is quite professional, and deliberately so. It matches the minimalist design Apple is known for, and discussions on the board show that the trolls went to great lengths to ensure that they match colors and font styles as closely as possible. The image of the phone matches the teaser image Apple used to promote iOS8 on their website before its launch. Even the wording is deliberate: Apple says iOS8 will be “the biggest release ever,” and the trolls claim Wave is “the next big thing.” Remarkably, the trolls even devised their own Wave app icon that stylistically imitates the “8” in the logo. All of these design choices add to the document’s ethos, convincing some unsuspecting users that Wave is a legitimate feature. If you didn’t know what happens when you microwave a phone, you could probably be convinced that this was real.

I turn now to tactical technical communication. Miles Kimball (2006) used the term to differentiate between institutional and user-produced technical communication. Using deCerteau’s concepts of “strategy” and “tactic” to differentiate the two, tactical technical communication reaches its audience “outside, between, and through” the institution. Scholarship on tactical technical communication tends to focus on instructional documentation. Kimball (2006) examined car user-produced car manuals. Colton, Holmes, and Walwema (2017) explored instructions produced by the hacker collective Anonymous. And Sarat-St. Peter (2017) studied instructions circulated by terrorists on how to make IEDs. While the Wave image is not instructional, it is still tactical. By coopting Apple’s design, logo, and images, the trolls are actively attempting to undermine Apple’s authority.

Colton, Holmes, and Walwema (2017) note that tactical tech com can be used as “forms of everyday resistance.” They paraphrase Ding (2009), outlining three actions tactical technical communicators seek to perform:

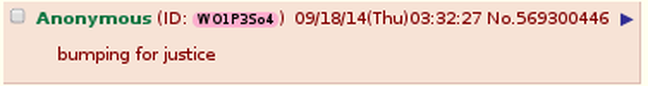

Kimball (2006) discusses the importance of narrative to instructional tactical tech com, stressing that it is less about how it should be done and more about “how I did it.” But in the case of trolls, the narrative worth examining is less in the documentation itself and more in their motivation for creating it. As previous research into the collective has shown, users on 4chan have constructed a narrative that paints them as outsiders to mainstream society. They feel marginalized and so engage in trolling acts (both singular and in raids) that attempt to flip this social order, allowing them brief moments where they can sit atop a social paradigm that they think typically undermines them. Some trolls might even consider it a form of social justice that disrupts the dominant cultural discourses. The screencap here demonstrates this with “bumping for justice,” which was a response to the post strategizing the circulation of the Wave document. Bumping means keeping the thread active on the main page longer.

Colton, Holmes, and Walwema (2017) note that tactical tech com can be used as “forms of everyday resistance.” They paraphrase Ding (2009), outlining three actions tactical technical communicators seek to perform:

- Create resistance

- Attract and sustain action to a cause

- Demand, and in some cases, succeed in obtaining redress.

Kimball (2006) discusses the importance of narrative to instructional tactical tech com, stressing that it is less about how it should be done and more about “how I did it.” But in the case of trolls, the narrative worth examining is less in the documentation itself and more in their motivation for creating it. As previous research into the collective has shown, users on 4chan have constructed a narrative that paints them as outsiders to mainstream society. They feel marginalized and so engage in trolling acts (both singular and in raids) that attempt to flip this social order, allowing them brief moments where they can sit atop a social paradigm that they think typically undermines them. Some trolls might even consider it a form of social justice that disrupts the dominant cultural discourses. The screencap here demonstrates this with “bumping for justice,” which was a response to the post strategizing the circulation of the Wave document. Bumping means keeping the thread active on the main page longer.

However, there are three issues with this narrative that point to how they pervert Ding’s and Colton, Holmes, and Walwema’s general actions of tactical tech com. First, as others have pointed out (Sparby, 2017; Phillips, 2015; Coleman, 2014; Stryker, 2011), the actual demographic of the anonymous collective is anything but oppressed: they are typically white, heteronormative men between the ages of 18 and 30 with economic privilege. They often engage in racist, misogynistic, and other bigoted discourses. The first action of tactical tech com is to “create resistance,” but social resistance is generally defined as exploited or disenfranchised people challenging the powers that oppress them. In many ways, the trolls represent the privileged demographic of society that resistance would typically challenge. At the very least, they are not as marginalized as their discourses would have us believe, so it is not clear what they are resisting.

Second, Sarat-St. Peter (2017) discusses tactical tech com narrative as a way that helps the user-producers empower other users. On the surface, this documentation appears to operate in this way, as a kind of “did you know” that fills in users on a little-known feature of widespread technology. But in practice, this documentation is anything but empowering. Despite their social justice narrative, the trolls are not targeting Apple in any grand anti-consumerist or anti-capitalist scheme. The second action of tactical tech com is “Attracting and sustaining action to a cause,” but it is not clear what their cause is. In fact, the Wave raid instead targets the very users that tactical tech com generally seeks to empower: the everyday user. Trolls typically characterize their motives for trolling as “doing it for the lulz,” or creating misfortune for someone so that they can laugh at it. Many trolls would probably define the cause behind a raid as “the lulz,” claiming that as their larger scheme. However, regardless of if their cause is “the lulz” or nonexistent, either serves as a subversion of the second action.

Finally, tactical tech com relies on trust between the user-producer and the end user: the documentation must embody some sort of ethos so that users will feel reasonably safe in their assumption that if they do what the document says then everything will be okay. This documentation certainly does that, but only because it successfully co-opts Apple’s ethos through using its logo and documentation style, including font and color scheme. In the end, it serves to build trust only to betray its users. This leads to the third action of tactical tech com: “Demand, and in some cases, succeed in obtaining redress.” Not only do the trolls not demand anything, at least not explicitly, but in the case of the Wave raid, they are not the ones who need redress. Instead, they actively cause harm to Apple users who fall for the hoax, nuke their phones, and now need an expensive replacement. The trolls cause the need for another group of users to seek redress, not themselves.

In short, to rephrase Kimball (2006) rephrasing deCerteau, the trolls inhabited Apple’s promotional document and remade it in their own image, and by doing so inhabited tactical tech com and remade it in their own image as well. Through subverting the three goals of tactical tech com, the trolls operated “outside, between, and through” Apple’s documentation and web presence by effectively creating a document that causes some of their users harm, both financially and potentially physically. Colton, Holmes, and Walwema (2017) explore hackers’ guides as examples of how tactical tech com is not always definitively ethical. They examine the gray area where these documents lie to conclude that they have the potential to cause unintended harm to both users and potentially mis-identified targets. Similarly, Sarat-St. Peter’s (2017) study of Jihadist instructions shows that, while tactical tech com instructions can be well-crafted and work toward accomplishing the three actions of tactical tech com, those documents can also be used to cause intentional harm to certain groups of individuals. Today, I built on these studies, showing that trolls can subvert—or perhaps we can go so far as to say “pervert”—the goals of tactical tech com all the while appearing to adhere to them. Only through understanding how trolls work can we see the subversion.

I end this presentation by reiterating: we can learn from trolls as technical communicators. I acknowledge that it’s difficult to catch trolls in the moment when they begin planning their raids, but when their raids are successful we are left with artifacts for analysis afterward. In the case of Wave, I was able to easily find through a Google search images of the documentation they created and their own screencaps of their conversations, the latter of which they often intentionally circulate as a pat on the back. As one of my earlier slides illustrated, images of their other raids are also easily found, and their instructional videos for drilling holes in the iPhone 7 is available on YouTube. Moving forward, the questions I’m interested in pursuing are,

Second, Sarat-St. Peter (2017) discusses tactical tech com narrative as a way that helps the user-producers empower other users. On the surface, this documentation appears to operate in this way, as a kind of “did you know” that fills in users on a little-known feature of widespread technology. But in practice, this documentation is anything but empowering. Despite their social justice narrative, the trolls are not targeting Apple in any grand anti-consumerist or anti-capitalist scheme. The second action of tactical tech com is “Attracting and sustaining action to a cause,” but it is not clear what their cause is. In fact, the Wave raid instead targets the very users that tactical tech com generally seeks to empower: the everyday user. Trolls typically characterize their motives for trolling as “doing it for the lulz,” or creating misfortune for someone so that they can laugh at it. Many trolls would probably define the cause behind a raid as “the lulz,” claiming that as their larger scheme. However, regardless of if their cause is “the lulz” or nonexistent, either serves as a subversion of the second action.

Finally, tactical tech com relies on trust between the user-producer and the end user: the documentation must embody some sort of ethos so that users will feel reasonably safe in their assumption that if they do what the document says then everything will be okay. This documentation certainly does that, but only because it successfully co-opts Apple’s ethos through using its logo and documentation style, including font and color scheme. In the end, it serves to build trust only to betray its users. This leads to the third action of tactical tech com: “Demand, and in some cases, succeed in obtaining redress.” Not only do the trolls not demand anything, at least not explicitly, but in the case of the Wave raid, they are not the ones who need redress. Instead, they actively cause harm to Apple users who fall for the hoax, nuke their phones, and now need an expensive replacement. The trolls cause the need for another group of users to seek redress, not themselves.

In short, to rephrase Kimball (2006) rephrasing deCerteau, the trolls inhabited Apple’s promotional document and remade it in their own image, and by doing so inhabited tactical tech com and remade it in their own image as well. Through subverting the three goals of tactical tech com, the trolls operated “outside, between, and through” Apple’s documentation and web presence by effectively creating a document that causes some of their users harm, both financially and potentially physically. Colton, Holmes, and Walwema (2017) explore hackers’ guides as examples of how tactical tech com is not always definitively ethical. They examine the gray area where these documents lie to conclude that they have the potential to cause unintended harm to both users and potentially mis-identified targets. Similarly, Sarat-St. Peter’s (2017) study of Jihadist instructions shows that, while tactical tech com instructions can be well-crafted and work toward accomplishing the three actions of tactical tech com, those documents can also be used to cause intentional harm to certain groups of individuals. Today, I built on these studies, showing that trolls can subvert—or perhaps we can go so far as to say “pervert”—the goals of tactical tech com all the while appearing to adhere to them. Only through understanding how trolls work can we see the subversion.

I end this presentation by reiterating: we can learn from trolls as technical communicators. I acknowledge that it’s difficult to catch trolls in the moment when they begin planning their raids, but when their raids are successful we are left with artifacts for analysis afterward. In the case of Wave, I was able to easily find through a Google search images of the documentation they created and their own screencaps of their conversations, the latter of which they often intentionally circulate as a pat on the back. As one of my earlier slides illustrated, images of their other raids are also easily found, and their instructional videos for drilling holes in the iPhone 7 is available on YouTube. Moving forward, the questions I’m interested in pursuing are,

- How does this raid and others contribute to or challenge our field?

- In particular, how do they contribute to or challenge “the relationship between technology, discourse, and people’s lives?”

- If trolls are co-opting and perverting tactical technical communication, do we have responsibilities to respond?

- And if so, what are they?

- And how do we do it?

References

de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Coleman, G. (2014). Hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy: The many faces of anonymous. New York: Verso.

Colton, J.S., Holmes, S., & Walwema, J. (2017). From noobguides to #OpKKK: Ethics of anonymous’ tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), pp. 59-75.

Ding, H. (2009). Rhetorics of alternative media in an emerging epidemic: SARS, censorship, and extra-institutional risk communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 19(4), pp. 327-350.

Kimball, M.A. (2006). Cars, culture, and tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 15(1), pp. 67-86.

Kimball, M.A. (2017). Tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), pp. 1-7.

Phillips, W. (2015). This is why we can’t have nice things: Mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sarat-St. Peter, H.A. (2017). ‘Make a bomb in the kitchen of your mom’: Jihadist tactical technical communication and the everyday practice of cooking. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), pp. 76-91.

Sparby, E.M. (2017). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric in 4chan’s collective identity. Computers and Composition, 45, pp. 5-97.

Stryker, C. (2011). Epic win for anonymous: How 4chan’s army conquered the web. New York: The Overlook Press.

Coleman, G. (2014). Hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy: The many faces of anonymous. New York: Verso.

Colton, J.S., Holmes, S., & Walwema, J. (2017). From noobguides to #OpKKK: Ethics of anonymous’ tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), pp. 59-75.

Ding, H. (2009). Rhetorics of alternative media in an emerging epidemic: SARS, censorship, and extra-institutional risk communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 19(4), pp. 327-350.

Kimball, M.A. (2006). Cars, culture, and tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 15(1), pp. 67-86.

Kimball, M.A. (2017). Tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), pp. 1-7.

Phillips, W. (2015). This is why we can’t have nice things: Mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sarat-St. Peter, H.A. (2017). ‘Make a bomb in the kitchen of your mom’: Jihadist tactical technical communication and the everyday practice of cooking. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), pp. 76-91.

Sparby, E.M. (2017). Digital social media and aggression: Memetic rhetoric in 4chan’s collective identity. Computers and Composition, 45, pp. 5-97.

Stryker, C. (2011). Epic win for anonymous: How 4chan’s army conquered the web. New York: The Overlook Press.